Trump Fires Security Chief Christopher Krebs

mercredi 18 novembre 2020 à 17:02President Trump on Tuesday fired his top election security official Christopher Krebs (no relation). The dismissal came via Twitter two weeks to the day after Trump lost an election he baselessly claims was stolen by widespread voting fraud.

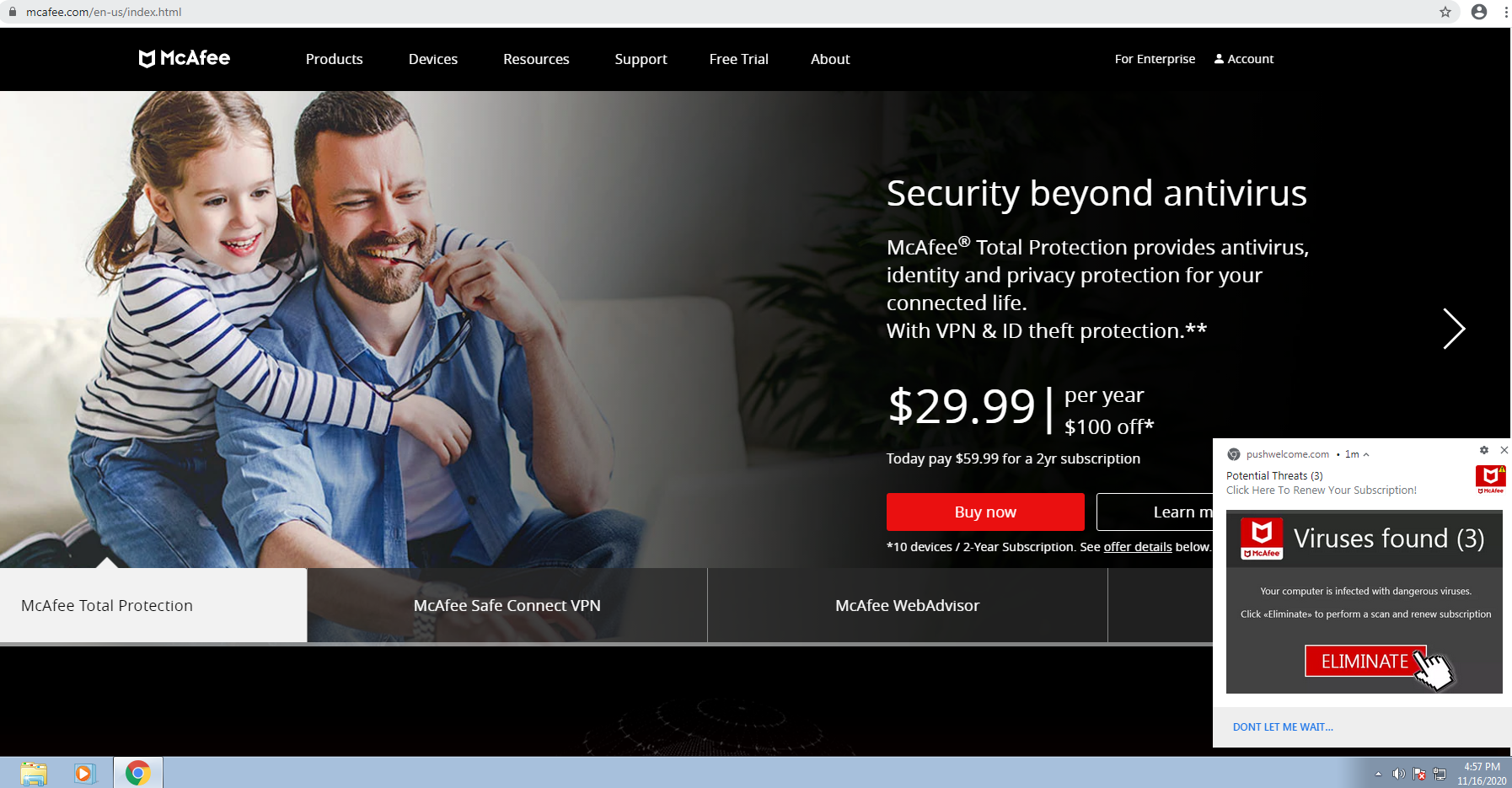

Chris Krebs. Image: CISA.

Krebs, 43, is a former Microsoft executive appointed by Trump to head the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), a division of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. As part of that role, Krebs organized federal and state efforts to improve election security, and to dispel disinformation about the integrity of the voting process.

Krebs’ dismissal was hardly unexpected. Last week, in the face of repeated statements by Trump that the president was robbed of re-election by buggy voting machines and millions of fraudulently cast ballots, Krebs’ agency rejected the claims as “unfounded,” asserting that “the November 3rd election was the most secure in American history.”

In a statement on Nov. 12, CISA declared “there is no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised.”

But in a tweet Tuesday evening, Trump called that assessment “highly inaccurate,” alleging there were “massive improprieties and fraud — including dead people voting, Poll watchers not allowed into polling locations, ‘glitches’ in the voting machines that changed votes from Trump to Biden, late voting, and many more.”

Twitter, as it has done with a remarkable number of the president’s tweets lately, flagged the statements as disputed.

By most accounts, Krebs was one of the more competent and transparent leaders in the Trump administration. But that same transparency may have cost him his job: Krebs’ agency earlier this year launched “Rumor Control,” a blog that sought to address many of the conspiracy theories the president has perpetuated in recent days.

Sen. Richard Burr, a Republican from North Carolina, said Krebs had done “a remarkable job during a challenging time,” and that the “creative and innovative campaign CISA developed to promote cybersecurity should serve as a model for other government agencies.”

Sen. Angus King, an Independent from Maine and co-chair of a commission to improve the nation’s cyber defense posture, called Krebs “an incredibly bright, high-performing, and dedicated public servant who has helped build up new cyber capabilities in the face of swiftly-evolving dangers.”

“By firing Mr. Krebs for simply doing his job, President Trump is inflicting severe damage on all Americans – who rely on CISA’s defenses, even if they don’t know it,” King said in a written statement. “If there’s any silver lining in this unjust decision, it’s this: I hope that President-elect Biden will recognize Chris’s contributions, and consult with him as the Biden administration charts the future of this critically important agency.”

KrebsOnSecurity has received more than a few messages these past two weeks from readers who wondered why the much-anticipated threat from Russian or other state-sponsored hackers never appeared to materialize in this election cycle.

That seems a bit like asking why the year 2000 came to pass with very few meaningful disruptions from the Y2K computer date rollover problem. After all, in advance of the new millennium, the federal government organized a series of task forces that helped coordinate readiness for the changeover, and to minimize the impact of any disruptions.

But the question also ignores a key goal of previous foreign election interference attempts leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential and 2018 mid-term elections. Namely, to sow fear, uncertainty, doubt, distrust and animosity among the electorate about the democratic process and its outcomes.

To that end, it’s difficult to see how anyone has done more to advance that agenda than President Trump himself, who has yet to concede the race and continues to challenge the result in state courts and in his public statements.