“BriansClub” Hack Rescues 26M Stolen Cards

mardi 15 octobre 2019 à 13:05“BriansClub,” one of the largest underground stores for buying stolen credit card data, has itself been hacked. The data stolen from BriansClub encompasses more than 26 million credit and debit card records taken from hacked online and brick-and-mortar retailers over the past four years, including almost eight million records uploaded to the shop in 2019 alone.

An ad for BriansClub has been using my name and likeness for years to peddle millions of stolen credit cards.

Last month, KrebsOnSecurity was contacted by a source who shared a plain text file containing what was claimed to be the full database of cards for sale both currently and historically through BriansClub[.]at, a thriving fraud bazaar named after this author. Imitating my site, likeness and namesake, BriansClub even dubiously claims a copyright with a reference at the bottom of each page: “© 2019 Crabs on Security.”

Multiple people who reviewed the database shared by my source confirmed that the same credit card records also could be found in a more redacted form simply by searching the BriansClub Web site with a valid, properly-funded account.

All of the card data stolen from BriansClub was shared with multiple sources who work closely with financial institutions to identify and monitor or reissue cards that show up for sale in the cybercrime underground.

The leaked data shows that in 2015, BriansClub added just 1.7 million card records for sale. But business would pick up in each of the years that followed: In 2016, BriansClub uploaded 2.89 million stolen cards; 2017 saw some 4.9 million cards added; 2018 brought in 9.2 million more.

Between January and August 2019 (when this database snapshot was apparently taken), BriansClub added roughly 7.6 million cards.

Most of what’s on offer at BriansClub are “dumps,” strings of ones and zeros that — when encoded onto anything with a magnetic stripe the size of a credit card — can be used by thieves to purchase electronics, gift cards and other high-priced items at big box stores.

As shown in the table below (taken from this story), many federal hacking prosecutions involving stolen credit cards will for sentencing purposes value each stolen card record at $500, which is intended to represent the average loss per compromised cardholder.

The black market value, impact to consumers and banks, and liability associated with different types of card fraud.

STOLEN BACK FAIR AND SQUARE

An extensive analysis of the database indicates BriansClub holds approximately $414 million worth of stolen credit cards for sale, based on the pricing tiers listed on the site. That’s according to an analysis by Flashpoint, a security intelligence firm based in New York City.

Allison Nixon, the company’s director of security research, said Flashpoint had help from numerous parties in crunching the numbers from the massive leaked database.

Nixon said the data suggests that between 2015 and August 2019, BriansClub sold roughly 9.1 million stolen credit cards, earning the site $126 million in sales (all sales are transacted in bitcoin).

If we take just the 9.1 million cards that were confirmed sold through BriansClub, we’re talking about $2.27 billion in likely losses at the $500 average loss per card figure from the Justice Department.

Also, it seems likely the total number of stolen credit cards for sale on BriansClub and related sites vastly exceeds the number of criminals who will buy such data. Shame on them for not investing more in marketing!

There’s no easy way to tell how many of the 26 million or so cards for sale at BriansClub are still valid, but the closest approximation of that — how many unsold cards have expiration dates in the future — indicates more than 14 million of them could still be valid.

The archive also reveals the proprietor(s) of BriansClub frequently uploaded new batches of stolen cards — some just a few thousand records, and others tens of thousands.

That’s because like many other carding sites, BriansClub mostly resells cards stolen by other cybercriminals — known as resellers or affiliates — who earn a percentage from each sale. It’s not yet clear how that revenue is shared in this case, but perhaps this information will be revealed in further analysis of the purloined database.

BRIANS CHAT

In a message titled “Your site is hacked,’ KrebsOnSecurity requested comment from BriansClub via the “Support Tickets” page on the carding shop’s site, informing its operators that all of their card data had been shared with the card-issuing banks.

I was surprised and delighted to receive a polite reply a few hours later from the site’s administrator (“admin”):

“No. I’m the real Brian Krebs here

Correct subject would be the data center was hacked.

Will get in touch with you on jabber. Should I mention that all information affected by the data-center breach has been since taken off sales, so no worries about the issuing banks.”

Flashpoint’s Nixon said a spot check comparison between the stolen card database and the card data advertised at BriansClub suggests the administrator is not being truthful in his claims of having removed the leaked stolen card data from his online shop.

The admin hasn’t yet responded to follow-up questions, such as why BriansClub chose to use my name and likeness to peddle millions of stolen credit cards.

Almost certainly, at least part of the appeal is that my surname means “crab” (or cancer), and crab is Russian hacker slang for “carder,” a person who engages in credit card fraud.

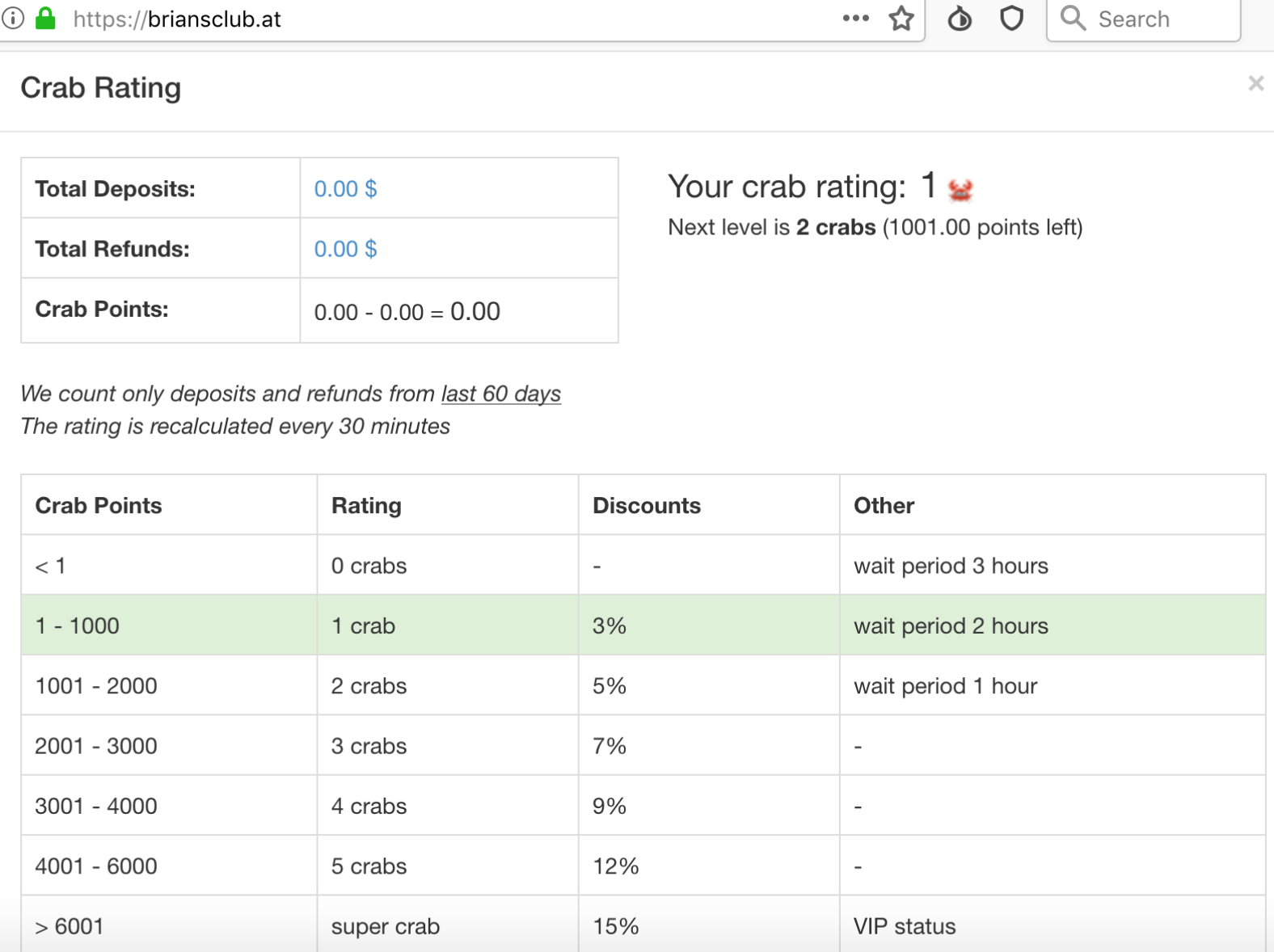

Many of the cards for sale on BriansClub are not visible to all customers. Those who wish to see the “best” cards in the shop need to maintain certain minimum balances, as shown in this screenshot.

HACKING BACK?

Nixon said breaches of criminal website databases often lead not just to prevented cybercrimes, but also to arrests and prosecutions.

“When people talk about ‘hacking back,’ they’re talking about stuff like this,” Nixon said. “As long as our government is hacking into all these foreign government resources, they should be hacking into these carding sites as well. There’s a lot of attention being paid to this data now and people are remediating and working on it.”

By way of example on hacking back, she pointed to the 2016 breach of vDOS — at the time the largest and most powerful service for knocking Web sites offline in large-scale cyberattacks.

Soon after vDOS’s database was stolen and leaked to this author, its two main proprietors were arrested. Also, the database added to evidence of criminal activity for several other individuals who were persons of interest in unrelated cybercrime investigations, Nixon said.

“When vDOS got breached, that basically reopened cases that were cold because [the leak of the vDOS database] supplied the final piece of evidence needed,” she said.

THE TARGET BREACH OF THE UNDERGROUND?

After many hours spent poring over this data, it became clear I needed some perspective on the scope and impact of this breach. As a major event in the cybercrime underground, was it somehow the reverse analog of the Target breach — which negatively impacted tens of millions of consumers and greatly enriched a large number of bad guys? Or was it more prosaic, like a Jimmy Johns-sized debacle?

For that insight, I spoke with Gemini Advisory, a New York-based company that works with financial institutions to monitor dozens of underground markets trafficking in stolen card data.

Andrei Barysevich, co-founder and CEO at Gemini, said the breach at BriansClub is certainly significant, given that Gemini currently tracks a total of 87 million credit and debit card records for sale across the cybercrime underground.

Gemini is monitoring most underground stores that peddle stolen card data — including such heavy hitters as Joker’s Stash, Trump’s Dumps, and BriansDump.

Contrary to popular belief, when these shops sell a stolen credit card record, that record is then removed from the inventory of items for sale. This allows companies like Gemini to determine roughly how many new cards are put up for sale and how many have sold.

Barysevich said the loss of so many valid cards may well impact how other carding stores compete and price their products.

“With over 78% of the illicit trade of stolen cards attributed to only a dozen of dark web markets, a breach of this magnitude will undoubtedly disturb the underground trade in the short term,” he said. “However, since the demand for stolen credit cards is on the rise, other vendors will undoubtedly attempt to capitalize on the disappearance of the top player.”

Liked this story and want to learn more about how carding shops operate? Check out Peek Inside a Professional Carding Shop. Want to help this site continue to produce useful, impactful journalism? Consider donating!

Happily, only about 15 percent of the bugs patched this week earned Microsoft’s most dire “critical” rating. Microsoft labels flaws critical when they could be exploited by miscreants or malware to seize control over a vulnerable system without any help from the user.

Happily, only about 15 percent of the bugs patched this week earned Microsoft’s most dire “critical” rating. Microsoft labels flaws critical when they could be exploited by miscreants or malware to seize control over a vulnerable system without any help from the user.