The Download on the DNC Hack

mercredi 4 janvier 2017 à 02:35Over the past few days, several longtime readers have asked why I haven’t written about two stories that have consumed the news media of late: The alleged Russian hacking attacks against the U.S. Democratic National Committee (DNC) and, more recently, the discovery of malware on a laptop at a Vermont power utility that has been attributed to Russian hacker groups.

I’ve avoided covering these stories mainly because I don’t have any original reporting to add to them, and because I generally avoid chasing the story of the day — preferring instead to focus on producing original journalism on cybercrime and computer security.

But there is another reason for my reticence: Both of these stories are so politically fraught that to write about them means signing up for gobs of vitriolic hate mail from readers who assume I have some political axe to grind no matter what I publish on the matter.

But there is another reason for my reticence: Both of these stories are so politically fraught that to write about them means signing up for gobs of vitriolic hate mail from readers who assume I have some political axe to grind no matter what I publish on the matter.

An article in Rolling Stone over the weekend aptly captures my unease with reporting on both of these stories in the absence of new, useful information (the following quote refers specifically to the Obama administration’s sanctions against Russia related to the DNC incident).

“The problem with this story is that, like the Iraq-WMD mess, it takes place in the middle of a highly politicized environment during which the motives of all the relevant actors are suspect,” Rolling Stone political reporter Matt Taibbi wrote. “Absent independent verification, reporters will have to rely upon the secret assessments of intelligence agencies to cover the story at all. Many reporters I know are quietly freaking out about having to go through that again.”

Alas, one can only nurse a New Year’s holiday vacation for so long. Here are some of the things I’ve been ruminating about over the past few days regarding each of these topics. Please be kind.

Gaining sufficient public support for a conclusion that other countries are responsible for hacking important U.S. assets can be difficult – even when the alleged aggressor is already despised and denounced by the entire civilized world.

The remarkable hacking of Sony Pictures Entertainment in late 2014 and the Obama administration’s quick fingering of hackers in North Korea as the culprits is a prime example: When the Obama administration released its findings that North Korean hackers were responsible for breaking into SPE, few security experts I spoke to about the incident were convinced by the intelligence data coming from the White House.

That seemed to change somewhat following the leak of a National Security Agency document which suggested the United States had planted malware capable of tracking the inner workings of the computers and networks used by the North’s hackers. Nevertheless, I’d wager that if we took a scientific poll among computer security experts today, a fair percentage of them probably still strongly doubt the administration’s conclusions.

If you were to ask those doubting experts to explain why they persist in their unbelief, my guess is you would find these folks break down largely into two camps: Those who believe the administration will never release any really detailed (and likely classified) information needed to draw a more definitive conclusion, and those who because of their political leanings tend to disbelieve virtually everything that comes out of the current administration.

Now, the American public is being asked to accept the White House’s technical assessment of another international hacking incident, only this time the apparent intention of said hacking is nothing less than to influence the outcome of a historically divisive presidential election in which the sitting party lost.

It probably doesn’t matter how many indicators of compromise and digital fingerprints the Obama administration releases on this incident: Chances are decent that if you asked a panel of security experts a year from now whether the march of time and additional data points released or leaked in the interim have influenced their opinion, you’ll find them just as evenly divided as they are today.

The mixed messages coming from the camp of President-elect Trump haven’t added any clarity to the matter, either. Trump has publicly mocked American intelligence assessments that Russia meddled with the U.S. election on his behalf, and said recently that he doubts the U.S. government can be certain it was hackers backed by the Russian government who hacked and leaked emails from the DNC.

However, one of Trump’s top advisers — former CIA Director James Woolsey — now says he believes the Russians (and possibly others) were in fact involved in the DNC hack.

It’s worth noting that the U.S. government has offered some additional perspective on why it is so confident in its conclusion that Russian military intelligence services were involved in the DNC hack. A White House fact sheet published alongside the FBI/DHS Joint Analysis Report (PDF) says the report “includes information on computers around the world that Russian intelligence services have co-opted without the knowledge of their owners in order conduct their malicious activity in a way that makes it difficult to trace back to Russia. In some cases, the cybersecurity community was aware of this infrastructure, in other cases, this information is newly declassified by the U.S. government.”

BREADCRUMBS

As I said in a tweet a few days back, the only remarkable thing about the hacking of the DNC is that the people responsible for protecting those systems somehow didn’t expect to be constantly targeted with email-based malware attacks. Lest anyone think perhaps the Republicans were better at anticipating such attacks, the FBI notified the Illinois Republican Party in June 2016 that some of its email accounts may have been hacked by the same group. The New York Times has reported that Russian hackers also broke into the DNC’s GOP counterpart — the Republican National Committee — but chose to release documents only on the Democrats.

I can’t say for certain if the Russian government was involved in directing or at least supporting attacks on U.S. political parties. But it seems to me they would be foolish not to have at least tried to get their least-hated candidate elected given how apparently easy it was to break in to the headquarters of both parties. Based on what I’ve learned over the past decade studying Russian language, culture and hacking communities, my sense is that if the Russians were responsible and wanted to hide that fact — they’d have left a trail leading back to some other country’s door.

That so many Russian hackers simply don’t bother to cover their tracks when attacking and plundering U.S. targets is a conclusion that many readers of this blog have challenged time and again, particularly with stories in my Breadcrumbs series. It’s too convenient and pat to be true, these detractors frequently claim. In my experience, however, if Russian hackers profiled on this blog were exposed because they did a poor job hiding their tracks, it’s usually because they didn’t even try.

In my view, this has more to do with the reality that there is very little chance these hackers will ever be held accountable for their crimes as long as they remain in Russia (or at least in former Soviet states that remain loyal to Russia). Take the case of Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev, one of the hackers named in the U.S. government’s assessment of those responsible for the DNC attack.

Bogachev, the alleged Zeus Trojan author, in undated photos.

A Russian hacker better known by his hacker alias “Slavik” and as the author of the ZeuS Trojan malware, Bogachev landed on the FBI’s 10-most-wanted list in 2014. The cybercriminal organization Bogchev allegedly ran was responsible for the theft of more than $100 million from banks and businesses worldwide that were infected with his ZeuS malware. That organization, dubbed the “Business Club,” had members spanning most of Russia’s 11 time zones.

Fox-IT, a Dutch security firm that infiltrated the Business Club’s back-end operations, said that beginning in late fall 2013 — about the time that conflict between Ukraine and Russia was just beginning to heat up — Slavik retooled his cyberheist botnet to serve as purely a spying machine, and began scouring infected systems in Ukraine for specific keywords in emails and documents that would likely only be found in classified documents.

Likewise, the keyword searches that Slavik used to scour bot-infected systems in Turkey suggested the botmaster was searching for specific files from the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the Turkish KOM – a specialized police unit. Fox-IT said it was clear that Slavik was looking to intercept communications about the conflict in Syria on Turkey’s southern border — one that Russia has supported by reportedly shipping arms into the region.

To date, Bogachev appears to be a free man, despite a $3 million bounty placed on his head by the FBI. This is likely because he’s remained inside Russia or at least within its sphere of protective influence. According to the FBI, Bogachev is known to enjoy boating and may be hiding out on a vessel somewhere in the Black Sea.

AN ‘INFORMATION NEXUS’

For the relatively few Russian hackers who do wind up in Russian prisons as a result of their cybercriminal activity, agreeing to hack another government might be the easiest way to get out of jail. The New York Times carried a story last month about how how Russian hackers like Bogachev often get recruited or coerced by the Russian government to work on foreign intelligence-gathering operations.

The story noted that while “much about Russia’s cyberwarfare program is shrouded in secrecy, details of the government’s effort to recruit programmers in recent years — whether professionals like…college students, or even criminals — are shedding some light on the Kremlin’s plan to create elite teams of computer hackers.”

According to Times reporter Andrew Kramer, a convicted hacker named Dmitry A. Artimovich was approached by Russian intelligence services while awaiting trial for building malware that was used in crippling online attacks. Artimovich told Kramer that in prison while awaiting trial he was approached by a cellmate who told Artimovich he could get out of jail if he agreed to work for the government.

Artimovich said he declined the offer. He was convicted of hacking and later spent a year in a Russian penal colony for his crimes. Artimovich also was a central figure in my book, Spam Nation: The Inside Story of Organized Cybercrime, from Global Epidemic to Your Front Door. His exploits, and that of his brother Igor, are partially detailed in various posts on this blog, but the long and the short of them is that Artimovich created a botnet that was used mainly for spam.

That is, until a friend of his hired him to launch a cyberattack against a company that provided payment processing services to Aeroflot, an airline that is 51 percent owned by the Russian government.

For many years, Artimovich used his botnet, dubbed “Festi” by security researchers, to pump spam promoting male enhancement drugs for a rogue online pharmacy operations called Rx-Promotion. Pavel Vrublevsky, RX-Promotion’s founder and the man who hired Artimovich to launch the cyberattack — also was convicted in the same trial, and sentenced to two years in a penal colony. However, Vrublevsky was inexplicably released after less than a year in Russia’s hinterlands.

Vrublevsky’s company ChronoPay was indirectly featured in another New York Times story about the hacking of the DNC. In September, The Times profiled Vladimir M. Fomenko, the 26-year-old manager of the web hosting firm King Servers, which U.S. cybersecurity firm ThreatConnect concluded was “an ‘information nexus‘ used by hackers suspected of working for Russian state security in cyberattacks on democratic processes in several countries, including Germany, Turkey and Ukraine, as well as the United States.” [Full disclosure: ThreatConnect has been an advertiser on this blog.]

An image from ChronoPay’s press release.

To bring this full circle, on Sept. 15, 2016, Fomenko issued a statement about the ThreatConnect report. That statement, originally written in Russian, was translated from Russian into English by Vrublevsky, and reposted on ChronoPay’s Web site.

“The analysis of the internal data allows King Servers to confidently refute any conclusions about the involvement of the Russian special services in this attack,” Fomenko said in his statement, which credits ChronoPay for the translation. “The company also reported that the attackers still owe the company $US290 for rental services and King Servers send an invoice for the payment to Donald Trump & Vladimir Putin, as well as the company reserves the right to send it to any other person who will be accused by mass media of this attack.”

FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE BOTNETS

If indeed those who hacked the DNC were recruited from the ranks of the cybercriminal community focused mainly on financial crime, I would not be surprised in the least. The Russian source who first introduced me to much of the cyber underground told me exactly this when we first met some years ago. He had just left the Russian military for a job at a computer security firm in Russia, and his job was to build a presence on all of the Russian-language cybercrime forums and learn the real-life identities of the major power players in that space.

That source, who won’t be named here because it would compromise his current position and create legal problems for him, said he routinely saw Russian intelligence services recruiting hackers on cybercrime forums — particularly for research into potential vulnerabilities in the software and hardware that powers various national power grids and other energy infrastructure.

“All these guys had interest in hacking government resources, including Russian [targets],” my source told me. “Several years ago I got to know one of these hackers who worked for Russian government, [and] he operated his [cybercrime] forum as a government honeypot for hiring hackers. They were hiring hackers to work in official government organizations.”

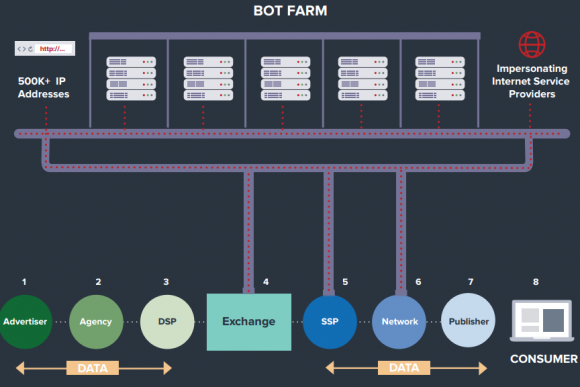

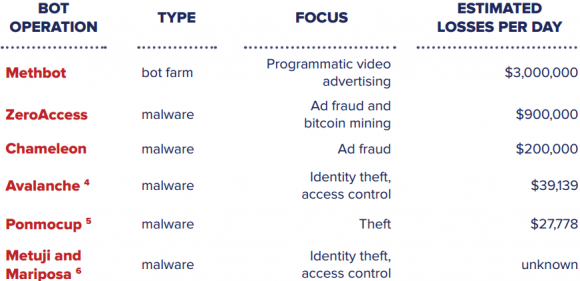

Initially, he said, the hackers targeted U.S. military installations and U.S. news media outlets, but eventually they turned their attention to collecting government and corporate secrets full-time. The source said the teams routinely used botnets for foreign intelligence gathering and counterintelligence, and frequently sought to infiltrate botnets that were suspected of being co-opted for the same purposes by other countries.

“Then they started attacking foreign-only targets, and even started their own VPN (virtual private networking) service for English-speaking customers so they could capture corporate data,” he told me. “They also ran a service for checking stolen PDFs and other documents for [proprietary] data and classified information. If something like Stuxnet destroys some power plant, I will think about these guys first. Now I use them as a source of information about foreign intelligence botnets, so I really don’t want them to be uncovered.”

ARE WE NOT ENTERTAINED?

Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising if many people remain unconvinced by the Joint Analysis Report released by the Obama administration. Fresh from an especially rancorous election muddled by the proliferation of “fake news” websites, public trust in the news media on technology and politics has to be at a historic low.

Last Friday, The Washington Post reported that Russian hackers penetrated the U.S. electricity grid through a utility in Vermont. The Post later significantly revised that story to clarify that malware tied to a Russian hacking group known to target companies in the energy sector had succeeded at infecting a single laptop at the utility, and that said laptop was never connected to the power grid.

To many already doubtful of the Obama administration’s claims about Russian hacking involvement in the election, The Post’s flub was yet another example of a left-leaning media establishment eager to capitalize on the Russian election-hacking narrative.

“From Russian hackers burrowed deep within the US electrical grid, ready to plunge the nation into darkness at the flip of a switch, an hour and a half later the story suddenly became that a single non-grid laptop had a piece of malware on it and that the laptop was not connected to the utility grid in any way,” wrote in Forbes.

Not that the American public is the best arbiter of truth and fiction. As Rolling Stone notes, despite the fact that election officials found virtually no voter fraud in the 2016 election, an Economist/YouGov poll conducted last month suggests that 50 percent of all Clinton voters believe the Russians hacked vote tallies. Not to be outdone, 62 percent of Trump voters said they believe Trump’s assertion that “millions” of undocumented immigrants likely voted in the election.

The public might also be deeply suspicious of hacking claims from a government that practically invented the art of meddling in foreign elections. As Nina Agrawal observes in The Los Angeles Times, the “U.S. has a long history of attempting to influence presidential elections in other countries – it’s done so as many as 81 times between 1946 and 2000, according to a database amassed by political scientist Dov Levin of Carnegie Mellon University.” Also, when it comes to hacking power plants, the U.S. and Israel have probably done more damage than anyone else with their incredibly complex Stuxnet virus, which was created as a weapon designed to delay Iran’s nuclear ambitions and opened a virtual Pandora’s Box.

In response to the alleged hacks, the Obama administration has expelled 35 Russian intelligence officials and imposed a series of economic sanctions on individuals and companies the administration says are connected to the DNC intrusions. The administration’s response has been criticized as lackluster and ineffectual, but it’s not entirely clear what else the White House could do publicly without risking retaliation in kind or worse.

However, the operative word there is “publicly.” Just as the administration almost certainly is not releasing all of the intelligence data that lead to its conclusion, I suspect that some of the U.S. response will materialize in ways that won’t be publicly acknowledged by this outgoing administration.

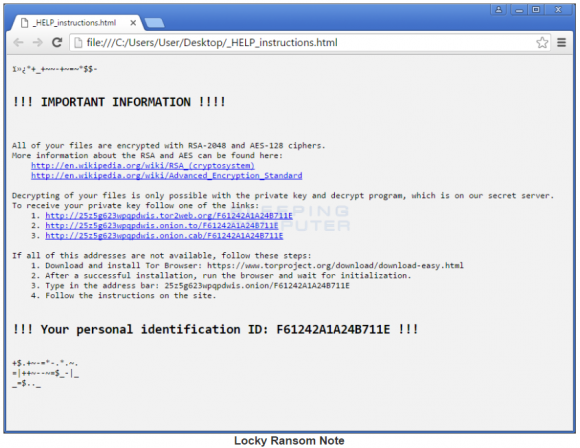

Villain: You MUST pay the ransom!

Villain: You MUST pay the ransom!