Alleged Member of Neo-Nazi Swatting Group Charged

samedi 11 janvier 2020 à 04:22Federal investigators on Friday arrested a Virginia man accused of being part of a neo-Nazi group that targeted hundreds of people in “swatting” attacks, wherein fake bomb threats, hostage situations and other violent scenarios were phoned in to police as part of a scheme to trick them into visiting potentially deadly force on a target’s address.

In July 2018, KrebsOnSecurity published the story Neo-Nazi Swatters Target Dozens of Journalists, which detailed the activities of a loose-knit group of individuals who had targeted hundreds of individuals for swatting attacks, including federal judges, corporate executives and almost three-dozen journalists (myself included).

An FBI affidavit unsealed this week identifies one member of the group as John William Kirby Kelley. According to the affidavit, Kelley was instrumental in setting up and maintaining the Internet Relay Chat (IRC) channel called “Deadnet” that was used by he and other co-conspirators to plan, carry out and document their swatting attacks.

Prior to his recent expulsion on drug charges, Kelley was a student studying cybersecurity at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va. Interestingly, investigators allege it was Kelley’s decision to swat his own school in late November 2018 that got him caught. Using the handle “Carl,” Kelley allegedly explained to fellow Deadnet members he hoped the swatting would get him out of having to go to class.

The FBI says Kelley used virtual private networking (VPN) services to hide his true Internet location and various voice-over-IP (VoIP) services to conduct the swatting calls. In the ODU incident, investigators say Kelley told ODU police that someone was armed with an AR-15 rifle and had placed multiple pipe bombs within the campus buildings.

Later that day, Kelley allegedly called ODU police again but forgot to obscure his real phone number on campus, and quickly apologized for making an accidental phone call. When authorities determined that the voice on the second call matched that from the bomb threat earlier in the day, they visited and interviewed the young man.

Investigators say Kelley admitted to participating in swatting calls previously, and consented to a search of his dorm room, wherein they found two phones, a laptop and various electronic storage devices.

The affidavit says one of the thumbs drive included multiple documents that logged statements made on the Deadnet IRC channel, which chronicled “countless examples of swatting activity over an extended period of time.” Those included videos Kelley allegedly recorded of his computer screen which showed live news footage of police responding to swatting attacks while he and other Deadnet members discussed the incidents in real-time on their IRC forum.

The FBI believes Kelley also was linked to a bomb threat incident in November 2018 at the predominantly African American Alfred Baptist Church in Old Town Alexandria, an incident that led to the church being evacuated during evening worship services while authorities swept the building for explosives.

The FBI affidavit was based in part on interviews with an unnamed co-conspirator, who told investigators that he and the others on Deadnet IRC are white supremacists and sympathetic to the neo-Nazi movement.

“The group’s neo-Nazi ideology is apparent in the racial tones throughout the conversation logs,” the affidavit reads. “Kelley and other co-conspirators are affiliated with or have expressed sympathy for Atomwafen Division,” an extremist group whose members are suspected of having committed multiple murders in the U.S. since 2017.

Investigators say on one of Kelley’s phones they found a photo of he and others in tactical gear holding automatic weapons next to pictures of Atomwaffen recruitment material and the neo-Nazi publication Siege.

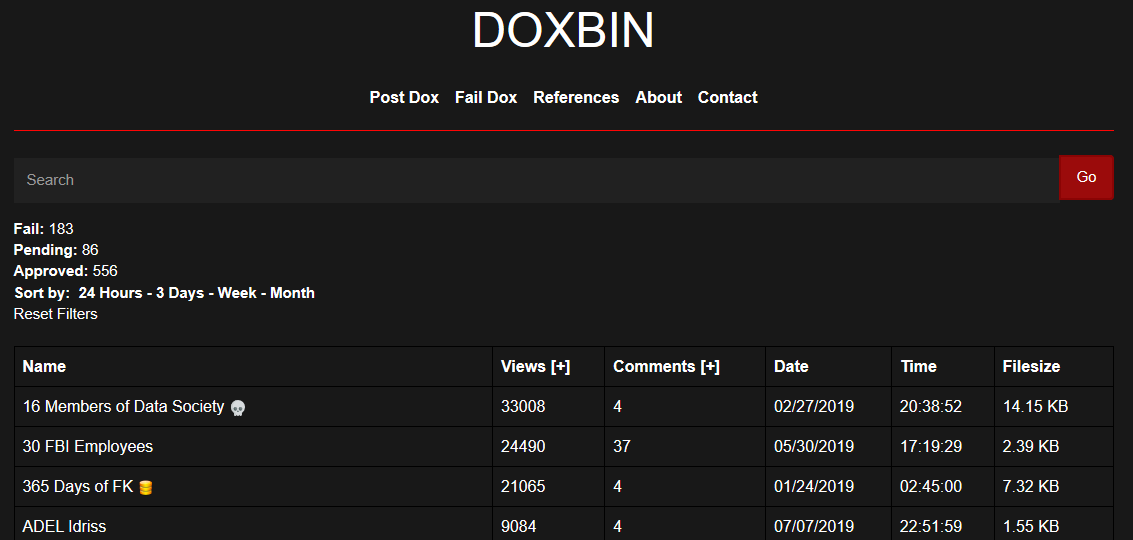

As I reported last summer, several Deadnet members maintained a site on the Dark Web called the “Doxbin,” which listed the names, addresses, phone number and often known IP addresses, Social Security numbers, dates of birth and other sensitive information on hundreds of people — and in some cases the personal information of the target’s friends and family. After those indexed on the Doxbin were successfully swatted, a blue gun icon would be added next to the person’s name.

One of the core members of the group on Deadnet — an individual who used the nickname “Chanz,” among others — stated that he was responsible for maintaining SiegeCulture, a white supremacist Web site that glorifies the writings of neo-Nazi James Mason (whose various books call on followers to start a violent race war in the United States).

Deadnet chat logs obtained by KrebsOnSecurity show that another key swatting suspect on Deadnet who used the handle “Zheme” told other IRC members in March 2019 that one of his friends had recently been raided by federal investigators for allegedly having connections to the person responsible for the mass shooting in October 2018 at the Tree of Life Jewish synagogue in Pittsburgh.

At one point last year, Zheme also reminded denizens of Deadnet about a court hearing in the murder trial of Sam Woodward, an alleged Atomwaffen member who’s been charged with killing a 19-year-old gay Jewish college student.

As reported by this author last year, Deadnet members targeted dozens of journalists whose writings they considered threatening to their worldviews. Indeed, one of the targets successfully swatted by Deadnet members was Pulitzer prize winning columnist Leonard G. Pitts Jr., whose personal information as listed on the Doxbin was annotated with a blue gun icon and the label “anti-white race/politics writer.”

In another Deadnet chat log seen by this author, Chanz admits to calling in a bomb threat at the UCLA campus following a speech by Milo Yiannopoulos. Chanz bragged that he did it to frame feminists at the school for acts of terrorism.

On a personal note, I sincerely hope this arrest is just the first of many to come for those involved in swatting attacks related to Deadnet and the Doxbin. KrebsOnSecurity has obtained information indicating that several members of my family also have been targeted for harassment and swatting by this group.

Finally, it’s important to note that while many people may assume that murders and mass shootings targeting people because of their race, gender, sexual preference or religion are carried out by so-called “lone wolf” assailants, the swatting videos created and shared by Deadnet members are essentially propaganda that hate groups can use to recruit new members to their cause.

The Washington Post reports that Kelley had his first appearance in federal court in Alexandria, Va. on Friday.

“His public defender did not comment on the allegations but said his client has ‘very limited funds,'” The Post’s courts reporter Rachel Weiner wrote.

The charge against Kelley of conspiracy to make threats carries up to five years in prison. The affidavit in Kelley’s arrest is available here (PDF).

Stories here have exposed countless scams, data breaches, cybercrooks and corporate stumbles. In the ten years since its inception, the site has attracted more than 37,000 newsletter subscribers, and nearly 100 million pageviews generated by roughly 40 million unique visitors.

Stories here have exposed countless scams, data breaches, cybercrooks and corporate stumbles. In the ten years since its inception, the site has attracted more than 37,000 newsletter subscribers, and nearly 100 million pageviews generated by roughly 40 million unique visitors.