110 Nursing Homes Cut Off from Health Records in Ransomware Attack

samedi 23 novembre 2019 à 06:02A ransomware outbreak has besieged a Wisconsin based IT company that provides cloud data hosting, security and access management to more than 100 nursing homes across the United States. The ongoing attack is preventing these care centers from accessing crucial patient medical records, and the IT company’s owner says she fears this incident could soon lead not only to the closure of her business, but also to the untimely demise of some patients.

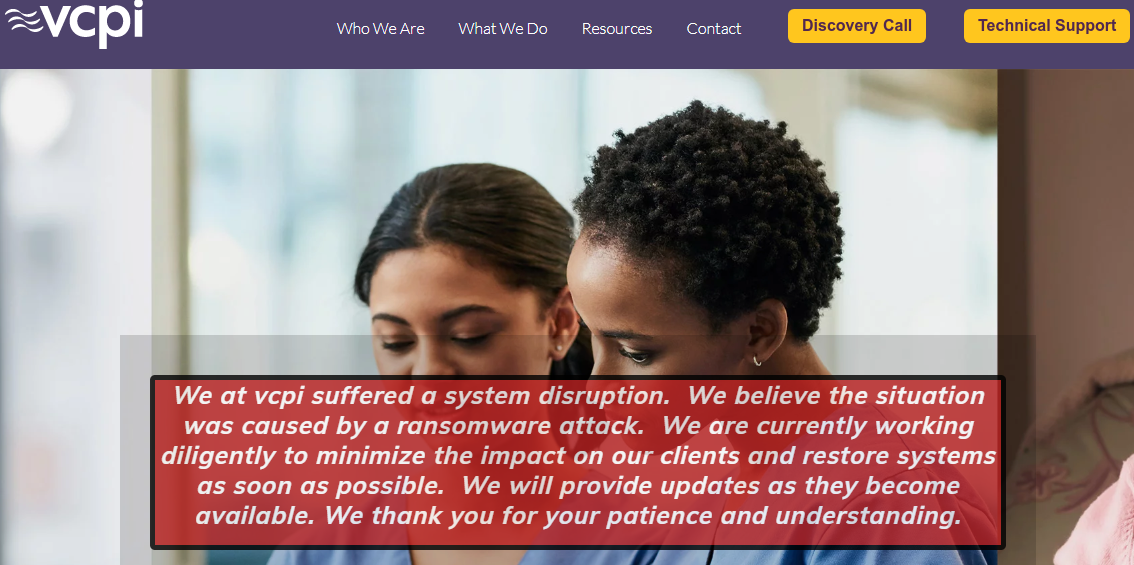

Milwaukee, Wisc. based Virtual Care Provider Inc. (VCPI) provides IT consulting, Internet access, data storage and security services to some 110 nursing homes and acute-care facilities in 45 states. All told, VCPI is responsible for maintaining approximately 80,000 computers and servers that assist those facilities.

At around 1:30 a.m. CT on Nov. 17, unknown attackers launched a ransomware strain known as Ryuk inside VCPI’s networks, encrypting all data the company hosts for its clients and demanding a whopping $14 million ransom in exchange for a digital key needed to unlock access to the files. Ryuk has made a name for itself targeting businesses that supply services to other companies — particularly cloud-data firms — with the ransom demands set according to the victim’s perceived ability to pay.

In an interview with KrebsOnSecurity today, VCPI chief executive and owner Karen Christianson said the attack had affected virtually all of their core offerings, including Internet service and email, access to patient records, client billing and phone systems, and even VCPI’s own payroll operations that serve nearly 150 company employees.

The care facilities that VCPI serves access their records and other systems outsourced to VCPI by using a Citrix-based virtual private networking (VPN) platform, and Christianson said restoring customer access to this functionality is the company’s top priority right now.

“We have employees asking when we’re going to make payroll,” Christianson said. “But right now all we’re dealing with is getting electronic medical records back up and life-threatening situations handled first.”

Christianson said her firm cannot afford to pay the ransom amount being demanded — roughly $14 million worth of Bitcoin — and said some clients will soon be in danger of having to shut their doors if VCPI can’t recover from the attack.

“We’ve got some facilities where the nurses can’t get the drugs updated and the order put in so the drugs can arrive on time,” she said. “In another case, we have this one small assisted living place that is just a single unit that connects to billing. And if they don’t get their billing into Medicaid by December 5, they close their doors. Seniors that don’t have family to go to are then done. We have a lot of [clients] right now who are like, ‘Just give me my data,’ but we can’t.”

The ongoing incident at VCPI is just the latest in a string of ransomware attacks against healthcare organizations, which typically operate on razor thin profit margins and have comparatively little funds to invest in maintaining and securing their IT systems.

Earlier this week, a 1,300-bed hospital in France was hit by ransomware that knocked its computer systems offline, causing “very long delays in care” and forcing staff to resort to pen and paper.

On Nov. 20, Cape Girardeau, Mo.-based Saint Francis Healthcare System began notifying patients about a ransomware attack that left physicians unable to access medical records prior to Jan. 1.

Tragically, there is evidence to suggest that patient outcomes can suffer even after the dust settles from a ransomware infestation at a healthcare provider. New research indicates hospitals and other care facilities that have been hit by a data breach or ransomware attack can expect to see an increase in the death rate among certain patients in the following months or years because of cybersecurity remediation efforts.

Researchers at Vanderbilt University‘s Owen Graduate School of Management took the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) list of healthcare data breaches and used it to drill down on data about patient mortality rates at more than 3,000 Medicare-certified hospitals, about 10 percent of which had experienced a data breach.

Their findings suggest that after data breaches as many as 36 additional deaths per 10,000 heart attacks occurred annually at the hundreds of hospitals examined. The researchers concluded that for care centers that experienced a breach, it took an additional 2.7 minutes for suspected heart attack patients to receive an electrocardiogram.

Companies hit by the Ryuk ransomware all too often are compromised for months or even years before the intruders get around to mapping out the target’s internal networks and compromising key resources and data backup systems. Typically, the initial infection stems from a booby-trapped email attachment that is used to download additional malware — such as Trickbot and Emotet.

This graphic from US-CERT depicts how the Emotet malware is typically used to lay the groundwork for a full-fledged ransomware infestation.

In this case, there is evidence to suggest that VCPI was compromised by one (or both) of these malware strains on multiple occasions over the past year. Alex Holden, founder of Milwaukee-based cyber intelligence firm Hold Security, showed KrebsOnSecurity information obtained from monitoring dark web communications which suggested the initial intrusion may have begun as far back as September 2018.

Holden said the attack was preventable up until the very end when the ransomware was deployed, and that this attack once again shows that even after the initial Trickbot or Emotet infection, companies can still prevent a ransomware attack. That is, of course, assuming they’re in the habit of regularly looking for signs of an intrusion.

“While it is clear that the initial breach occurred 14 months ago, the escalation of the compromise didn’t start until around November 15th of this year,” Holden said. “When we looked at this in retrospect, during these three days the cybercriminals slowly compromised the entire network, disabling antivirus, running customized scripts, and deploying ransomware. They didn’t even succeed at first, but they kept trying.”

VCPI’s CEO said her organization plans to publicly document everything that has happened so far when (and if) this attack is brought under control, but for now the company is fully focused on rebuilding systems and restoring operations, and on keeping clients informed at every step of the way.

“We’re going to make it part of our strategy to share everything we’re going through,” Christianson said, adding that when the company initially tried several efforts to sidestep the intruders their phone systems came under concerted assault. “But we’re still under attack, and as soon as we can open, we’re going to document everything.”