Earlier this month a hacker released the source code for Mirai, a malware strain that was used to launch a historically large 620 Gbps denial-of-service attack against this site in September. That attack came in apparent retribution for a story here which directly preceded the arrest of two Israeli men for allegedly running an online attack for hire service called vDOS. Turns out, the site where the Mirai source code was leaked had some very interesting things in common with the place vDOS called home.

The domain name where the Mirai source code was originally placed for download — santasbigcandycane[dot]cx — is registered at the same domain name registrar that was used to register the now-defunct DDoS-for-hire service vdos-s[dot]com.

Normally, this would not be remarkable, since most domain registrars have thousands or millions of domains in their stable. But in this case it is interesting mainly because the registrar used by both domains — a company called namecentral.com — has apparently been used to register just 38 domains since its inception by its current owner in 2012, according to a historic WHOIS records gathered by domaintools.com (for the full list see this PDF).

What’s more, a cursory look at the other domains registered via namecentral.com since then reveals a number of other DDoS-for-hire services, also known as “booter” or “stresser” services.

It’s extremely odd that someone would take on the considerable cost and trouble of creating a domain name registrar just to register a few dozen domains. It costs $3,500 to apply to the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) for a new registrar authority. The annual fee for being an ICANN-approved registrar is $4,000, and then there’s a $800 quarterly fee for smaller registrars. In short, domain name registrars generally need to register many thousands of new domains each year just to turn a profit.

Many of the remaining three dozen or so domains registered via Namecentral over the past few years are tied to vDOS. Before vDOS was taken offline it was massively hacked, and a copy of the user and attack database was shared with KrebsOnSecurity. From those records it was easy to tell which third-party booter services were using vDOS’s application programming interface (API), a software function that allowed them to essentially resell access to vDOS with their own white-labeled stresser.

And a number of those vDOS resellers were registered through Namecentral, including 83144692[dot].com — a DDoS-for-hire service marketed at Chinese customers. Another Namecentral domain — vstress.net — also was a vDOS reseller.

Other DDoS-for-hire domains registered through Namecentral include xboot[dot]net, xr8edstresser[dot]com, snowstresser[dot]com, ezstress[dot]com, exilestress[dot]com, diamondstresser[dot]net, dd0s[dot]pw, rebelsecurity[dot]net, and beststressers[dot]com.

WHO RUNS NAMECENTRAL?

Namecentral’s current owner is a 19-year-old California man by the name of Jesse Wu. Responding to questions emailed from KrebsOnSecurity, Wu said Namecentral’s policy on abuse was inspired by Cloudflare, the DDoS protection company that guards Namecentral and most of the above-mentioned DDoS-for-hire sites from attacks of the very kind they sell.

“I’m not sure (since registrations are automated) but I’m going to guess that the reason you’re interested in us is because some stories you’ve written in the past had domains registered on our service or otherwise used one of our services,” Wu wrote.

“We have a policy inspired by Cloudflare’s similar policy that we ourselves will remain content-neutral and in the support of an open Internet, we will almost never remove a registration or stop providing services, and furthermore we’ll take any effort to ensure that registrations cannot be influenced by anyone besides the actual registrant making a change themselves – even if such website makes us uncomfortable,” Wu said. “However, as a US based company, we are held to US laws, and so if we receive a valid court issued order to stop providing services to a client, or to turn over/disable a domain, we would happily comply with such order.”

Wu’s message continued:

“As of this email, we have never received such an order, we have never been contacted by any law enforcement agency, and we have never even received a legitimate, credible abuse report. We realize this policy might make us popular with ‘dangerous’ websites but even then, if we denied them services, simply not providing them services would not make such website stop existing, they would just have to find some other service provider/registrar or change domains more often. Our services themselves cannot be used for anything harmful – a domain is just a string of letters, and the rest of our services involve website/ddos protection/ecommerce security services designed to protect websites.”

Taking a page from Cloudflare, indeed. I’ve long taken Cloudflare to task for granting DDoS protection for countless DDoS-for-hire services, to no avail. I’ve maintained that Cloudflare has a blatant conflict of interest here, and that the DDoS-for-hire industry would quickly blast itself into oblivion because the proprietors of these attack services like nothing more than to turn their attack cannons on each other. Cloudflare has steadfastly maintained that picking and choosing who gets to use their network is a slippery slope that it will not venture toward.

Although Mr. Wu says he had nothing to do with the domains registered through Namecentral, public records filed elsewhere raise serious unanswered questions about that claim.

In my Sept. 8 story, Israeli Online Attack Service Earned $600,000 in Two Years, I explained that the hacked vDOS database indicated the service was run by two 18-year-old Israeli men. At some point, vDOS decided to protect all customer logins to the service with an extended validation (EV) SSL certificate. And for that, it needed to show it was tied to an actual corporate entity.

My investigation into those responsible for supporting vDOS began after I took a closer look at the SSL certificate that vDOS-S[dot]com used to encrypt customer logins. On May 12, 2015, Digicert.com issued an EV SSL certificate for vDOS, according to this record.

As we can see, whoever registered that EV cert did so using the business name VS NETWORK SERVICES LTD, and giving an address in the United Kingdom of 217 Blossomfield Rd., Solihull, West Midlands.

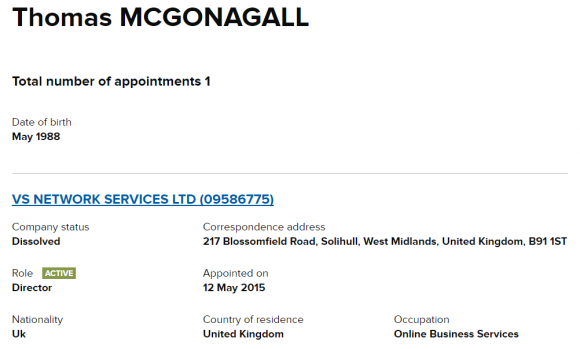

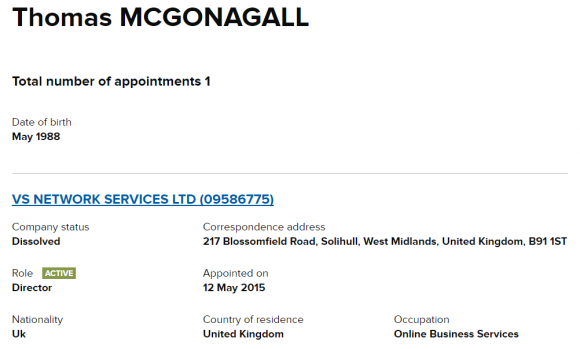

Who owns VS NETWORK SERVICES LTD? According this record from Companies House UK — an official ledger of corporations located in the United Kingdom — the director of the company was listed as one Thomas McGonagall.

Records from Companies House UK on the firm responsible for registering vDOS’s SSL certificate.

This individual gave the same West Midlands address, stating that he was appointed to VS Network Services on May 12, 2015, and that his birthday was in May 1988. A search in Companies House for Thomas McGonagall shows that a person by that same name and address also was listed that very same day as a director for a company called REBELSECURITY LTD.

If we go back even further into the corporate history of this mysterious Mr. McGonagall we find that he was appointed director of NAMECENTRAL LTD on August 18, 2014. Mr. McGonagall’s birthday is listed as December 1995 in this record, and his address is given as 29 Wigorn Road, 29 Wigorn Road, Smethwick, West Midlands, United Kingdom, B67 5HL. Also on that same day, he was appointed to run EZSTRESS LTD, a company at the same Smethwick, West Midlands address.

Strangely enough, those company names correspond to other domains registered through Namecentral around the same time the companies were created, including rebelsecurity[dot]net, ezstress[dot]net.

Asked to explain the odd apparent corporate connections between Namecentral, vDOS, EZStress and Rebelsecurity, Wu chalked that up to an imposter or potential phishing attack.

“I’m not sure who that is, and we are not affiliated with Namecentral Ltd.,” he wrote. “I looked it up though and it seems like it is either closed or has never been active. From what you described it could be possible someone set up shell companies to try and get/resell EV certs (and someone’s failed attempt to set up a phishing site for us – thanks for the heads up).”

Interestingly, among the three dozen or so domains registered through Namecentral.com is “certificateavenue.com,” a site that until recently included nearly identical content as Namecentral’s home page and appears to be aimed at selling EV certs. Certificateavenue.com was responding as of early-October, but it is no longer online.

I also asked Wu why he chose to become a domain registrar when it appeared he had very few domains to justify the substantial annual costs of maintaining a registrar business.

“Like most other registrars, we register domains only as a value added service,” he replied via email. “We have more domains than that (not willing to say exactly how many) but primarily we make our money on our website/ddos protection/ecommerce protection.”

Now we were getting somewhere. Turns out, Wu isn’t really in the domain registrar business — not for the money, anyway. The real money, as his response suggests, is in selling DDoS protection against the very DDoS-for-hire services he is courting with his domain registration service.

Asked to reconcile his claim for having a 100 percent hands-off, automated domain registration system with the fact that Namecentral’s home page says the company doesn’t actually have a way to accept automated domain name registrations (like most normal domain registrars), Wu again had an answer.

“Our site says we only take referred registrations, meaning that at the moment we’re asking that another prior customer referred you to open a new account for our services, including if you’d like a reseller account,” he wrote.

CAUGHT IN A FIB?

I was willing to entertain the notion that perhaps Mr. Wu was in fact the target of a rather elaborate scam of some sort. That is, until I stumbled upon another company that was registered in the U.K. to Mr. McGonagall.

That other company —SIMPLIFYNT LTD — was registered by Mr. McGonagall on October 29, 2014. Turns out, almost the exact same information included in the original Web site registration records for Jesse Wu’s purchase of Namecentral.com was used for the domain simplifynt.com, which also was registered on Oct. 29, 2014. I initially missed this domain because it was not registered through Namecentral. If someone had phished Mr. Wu in this case, they had been very quick to the punch indeed.

In the simplyfynt.com domain registration records, Jesse Wu gave his email address as jesse@jjdev.ru. That domain is no longer online, but a cached copy of it at archive.org shows that it was once a Web development business. That cached page lists yet another contact email address: sales@jjdevelopments.org.

I ordered a reverse WHOIS lookup from domaintools.com on all historic Web site registration records that included the domain “jjdevelopments.org” anywhere in the records. The search returned 15 other domains, including several more apparent DDoS-for-hire domains such as twbooter69.com, twbooter3.com, ratemyddos.com and desoboot.com.

Among the oldest and most innocuous of those 15 domains was maplemystery.com, a fan site for a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) called Maple Story. Another historic record lookup ordered from domaintools.com shows that maplemystery.com was originally registered in 2009 to a “Denny Ng.” As it happens, Denny Ng is listed as the co-owner of the $1.6 million Walnut, Calif. home where Jesse until very recently lived with his mom Cindy Wu (Jesse is now a student at the University of California, San Diego).

WHO IS DATAWAGON?

Another domain of interest that was secured via Namecentral is datawagon.net. Registered by 19-year-old Christopher J. “CJ” Sculti Jr., Datawagon also bills itself as a DDoS mitigation firm. It appears Mr. Sculti built his DDoS protection empire out of his parents’ $2.6 million home in Rye, NY. He’s now a student at Clemson University, according to his Facebook page.

CJ Sculti Jr.’s Facebook profile photo. Sculti is on pictured on the right.

As I noted in my story DDoS Mitigation Firm Has a History of Hijacks, Sculti earned his 15 minutes of fame in 2015 when he lost a cybersquatting suit with Dominos Pizza after registering the domain dominos.pizza (another domain registered via Namecentral).

Around that time, Sculti contacted KrebsOnSecurity via Skype, asking if I’d be interested in writing about this cybersquatting dispute with Dominos. In that conversation, Sculti — apropos of nothing — admits to having just scanned the Internet for routers that were known to be protected by little more than the factory-default usernames and passwords.

Sculti goes on to brag that his scan revealed a quarter-million routers that were vulnerable, and that he then proceeded to upload some kind software to each vulnerable system. Here’s a snippet of that chat conversation, which is virtually one-sided.

July 7, 2015:

21:37 CJ http://krebsonsecurity.com/2015/06/crooks-use-hacked-routers-to-aid-cyberheists/

21:37 CJ

vulnerable routers are a HUGE issue

21:37 CJ

a few months ago

21:37 CJ

I scanned the internet with a few sets of defualt logins

21:37 CJ

for telnet

21:37 CJ

and I was able to upload and execute a binary

21:38 CJ

on 250k devices

21:38 CJ

most of which were routers

21:38 Brian Krebs

o_0

21:38 CJ

yea

21:38 CJ

i’m surprised no one has looked into that yet

21:38 CJ

but

21:39 CJ

it’s a huge issue lol

21:39 CJ

that’s tons of bandwidth

21:39 CJ

that could be potentially used

21:39 CJ

in the wrong way

21:39 CJ

lol

—

Tons of bandwidth, indeed. The very next time I heard from Sculti was the same day I published the above-mentioned story about Datawagon’s relationship to BackConnect Inc., a company that admitted to hijacking 256 Internet addresses from vDOS’s hosting provider in Bulgaria — allegedly to defend itself against a monster attack allegedly launched by vDOS’s proprietors.

Sculti took issue with how he was portrayed in that report, and after a few terse words were exchanged, I blocked his Skype account from further communicating with mine. Less than an hour after that exchange, my Skype inbox was flooded with thousands of bogus contact requests from hacked or auto-created Skype accounts.

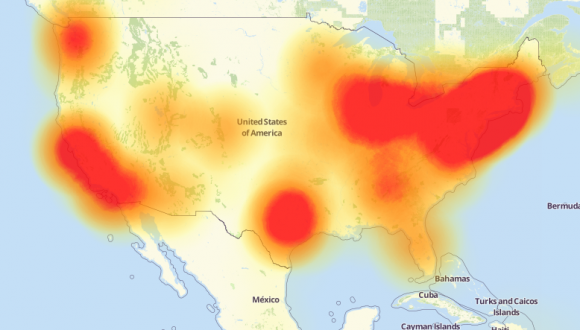

Less than six hours after that conversation, my site came under the biggest DDoS attack the Internet had ever witnessed at the time, an attack that experts have since traced back to a large botnet of IoT devices infected with Mirai.

As I wrote in the story that apparently incurred Sculti’s ire, Datawagon — like BackConnect — also has a history of hijacking broad swaths of Internet address space that do not belong to it. That listing came not long after Datawagon announced that it was the rightful owner of some 256 Internet addresses (1.3.3.0/24) that had long been dormant.

The Web address 1.3.3.7 currently does not respond to browser requests, but it previously routed to a page listing the core members of a hacker group calling itself the Money Team. Other sites also previously tied to that Internet address include numerous DDoS-for-hire services, such as nazistresser[dot]biz, exostress[dot]in, scriptkiddie[dot]eu, packeting[dot]eu, leet[dot]hu, booter[dot]in, vivostresser[dot]com, shockingbooter[dot]com and xboot[dot]info, among others.

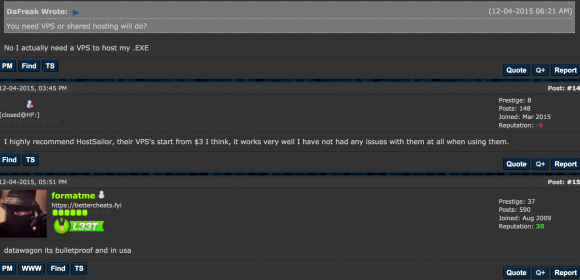

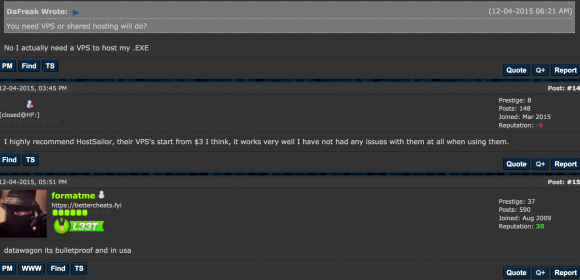

Datawagon has earned a reputation on hacker forums as a “bulletproof” hosting provider — one that will essentially ignore abuse complaints from other providers and turn a blind eye to malicious activity perpetrated by its customers. In the screenshot below — taken from a thread on Hackforums where Datawagon was suggested as a reliable bulletproof hoster — the company is mentioned in the same vein as HostSailor, another bulletproof provider that has been the source of much badness (as well as legal threats against this author).

In yet another Hackforums discussion thread from June 2016 titled “VPS [virtual private servers] that allow DDoS scripts,” one user recommends Datawagon. “I use datawagon.net. They allow anything.”

Last year, Sculti formed a company in Florida along with a self-avowed spammer. Perhaps unsurprisingly, anti-spam group Spamhaus soon listed virtually all of Datawagon’s Internet address space as sources of spam.

Are either Mr. Wu or Mr. Sculti behind the Mirai botnet attacks? I cannot say. But I’d be willing to bet money that one or both of them knows who is. In any case, it would appear that both men may have hit upon a very lucrative business model. More to come.

That’s right: If you purchased a “Never Hillary” poster or donated funds to the NRSC through

That’s right: If you purchased a “Never Hillary” poster or donated funds to the NRSC through