What the Marriott Breach Says About Security

samedi 1 décembre 2018 à 22:16We don’t yet know the root cause(s) that forced Marriott this week to disclose a four-year-long breach involving the personal and financial information of 500 million guests of its Starwood hotel properties. But anytime we see such a colossal intrusion go undetected for so long, the ultimate cause is usually a failure to adopt the most important principle in cybersecurity defense that applies to both corporations and consumers: Assume you are compromised.

TO COMPANIES

For companies, this principle means accepting the notion that it is no longer possible to keep the bad guys out of your networks entirely. This doesn’t mean abandoning all tenets of traditional defense, such as quickly applying software patches and using technologies to block or at least detect malware infections.

It means accepting that despite how many resources you expend trying to keep malware and miscreants out, all of this can be undone in a flash when users click on malicious links or fall for phishing attacks. Or a previously unknown security flaw gets exploited before it can be patched. Or any one of a myriad other ways attackers can win just by being right once, when defenders need to be right 100 percent of the time.

The companies run by leaders and corporate board members with advanced security maturity are investing in ways to attract and retain more cybersecurity talent, and arranging those defenders in a posture that assumes the bad guys will get in.

This involves not only focusing on breach prevention, but at least equally on intrusion detection and response. It starts with the assumption that failing to respond quickly when an adversary gains an initial foothold is like allowing a tiny cancer cell to metastasize into a much bigger illness that — left undetected for days, months or years — can cost the entire organism dearly.

The companies with the most clueful leaders are paying threat hunters to look for signs of new intrusions. They’re reshuffling the organizational chart so that people in charge of security report to the board, the CEO, and/or chief risk officer — anyone but the Chief Technology Officer.

They’re constantly testing their own networks and employees for weaknesses, and regularly drilling their breach response preparedness (much like a fire drill). And, apropos of the Marriott breach, they are finding creative ways to cut down on the volume of sensitive data that they need to store and protect.

TO INDIVIDUALS

Likewise for individuals, it pays to accept two unfortunate and harsh realities:

Reality #1: Bad guys already have access to personal data points that you may believe should be secret but which nevertheless aren’t, including your credit card information, Social Security number, mother’s maiden name, date of birth, address, previous addresses, phone number, and yes — even your credit file.

Reality #2: Any data point you share with a company will in all likelihood eventually be hacked, lost, leaked, stolen or sold — usually through no fault of your own. And if you’re an American, it means (at least for the time being) your recourse to do anything about that when it does happen is limited or nil.

Marriott is offering affected consumers a year’s worth of service from a company owned by security firm Kroll that advertises the ability to scour cybercrime underground markets for your data. Should you take them up on this offer? It probably can’t hurt as long as you’re not expecting it to prevent some kind of bad outcome. But once you’ve accepted Realities #1 and #2 above it becomes clear there is nothing such services could tell you that you don’t already know.

Once you’ve owned both of these realities, you realize that expecting another company to safeguard your security is a fool’s errand, and that it makes far more sense to focus instead on doing everything you can to proactively prevent identity thieves, malicious hackers or other ne’er-do-wells from abusing access to said data.

This includes assuming that any passwords you use at one site will eventually get hacked and leaked or sold online (see Reality #2), and that as a result it is an extremely bad idea to re-use passwords across multiple Web sites. For example, if you used your Starwood password anywhere else, that other account you used it at is now at a much higher risk of getting compromised.

By the way, if you are the type of person who likes to re-use passwords, then you definitely need to be using a password manager, which helps you pick and remember strong passwords/passphrases and essentially lets you use the same strong master password/passphrase across all Web sites.

The “assume you’re compromised” philosophy involves freezing your credit files with the major credit bureaus, and regularly ordering free copies of your credit file from annualcreditreport.com to make sure nobody is monkeying with your credit (except you).

It means planting your flag at various online services before fraudsters do it for you, such as at the Social Security Administration, U.S. Postal Service, Internal Revenue Service, your mobile provider, and your Internet service provider (ISP).

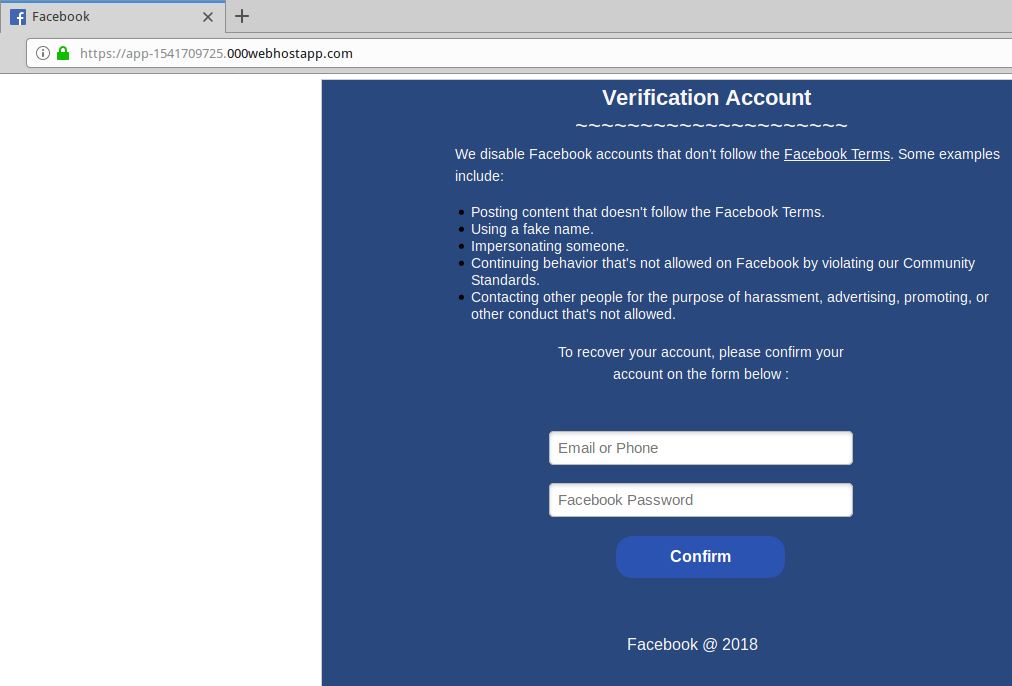

Assuming compromise means placing very little trust or confidence in anything that comes to you via email. In the context of this Marriott/Starwood breach, for example, consider all the data points that attackers may now have to make a phishing or malware attack more likely to be successful: Your Starwood account number, your address, phone number, email address, passport number, dates and times of your reservations, and credit card information.

How hard would it be for someone to craft an email that warns of a problem with a recent reservation or with your Starwood account, urging you to click a booby trapped link or attachment to learn more? Now imagine that such targeted emails can come from any brand with whom you’ve done business (for a refresher, see Reality #2 above).

Assuming you’re compromised means beefing up your passwords by adopting more robust multi-factor authentication — and perhaps even transitioning away from SMS/text messages for multifactor toward more secure app- or key-based options.

TOUGH TRADE-OFFS

If the advice above sounds inconvenient, unfair and expensive for all involved, congratulations: You are well on your way to internalizing Realities #1 and #2. For better or worse, being a savvy consumer means constantly having to make difficult trade-offs between security, privacy, and convenience.

Oh, and you generally only get to pick two out of three of these qualities. Same goes for the trio of high-speed, high-quality, and low-cost. Or good, fast, and cheap. Again, pick two. You get the idea.

Unfortunately, these transactions become even more lopsided and difficult to weigh when one party to them always selects the same trade-off (e.g., fast, low-cost, and convenient). Right now, it sure seems like there aren’t a lot of consequences when huge companies that ought to know better screw up massively on security, leaving consumers and their paying customers to clean up the mess.

I don’t know how many more big-time privacy and security debacles we need to convince our nation’s leaders that perhaps we should enshrine in law some basic standards of care for how companies handle and secure consumer data, and what rights and expectations consumers should have when companies fail to meet those standards. Because it’s clear that unless and until this happens, some subset of businesses out there will continue to make the most expedient and short-sighted trade-offs available to them, regardless of the impact to their customers and the public at large.

On this point, as with many others related to Internet security and privacy, I found it hard to argue with the opinion of my home state Senator Mark Warner (D-Va.), who observed:

“It seems like every other day we learn about a new mega-breach affecting the personal data of millions of Americans. Rather than accepting this trend as the new normal, this latest incident should strengthen Congress’ resolve. We must pass laws that require data minimization, ensuring companies do not keep sensitive data that they no longer need. And it is past time we enact data security laws that ensure companies account for security costs rather than making their consumers shoulder the burden and harms resulting from these lapses.”