Did the Clinton Email Server Have an Internet-Based Printer?

jeudi 26 mai 2016 à 23:50The Associated Press today points to a remarkable footnote in a recent State Department inspector general report on the Hillary Clinton email scandal: The mail was managed from the vanity domain “clintonemail.com.” But here’s a potentially more explosive finding: A review of the historic domain registration records for that domain indicates that whoever built the private email server for the Clintons also had the not-so-bright idea of connecting it to an Internet-based printer.

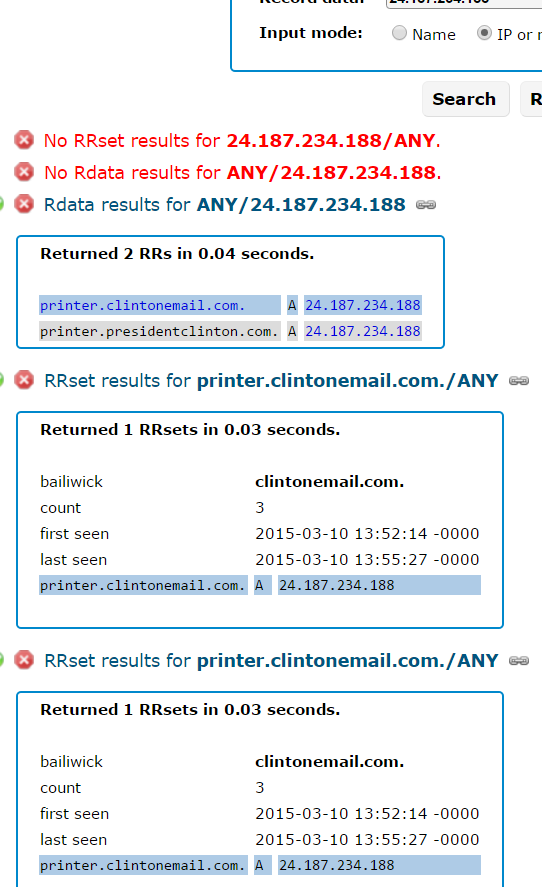

According to historic Internet address maps stored by San Mateo, Calif. based Farsight Security, among the handful of Internet addresses historically assigned to the domain “clintonemail.com” was the numeric address 24.187.234.188. The subdomain attached to that Internet address was….wait for it…. “printer.clintonemail.com“.

Interestingly, that domain was first noticed by Farsight in March 2015, the same month the scandal broke that during her tenure as United States Secretary of State Mrs. Clinton exclusively used her family’s private email server for official communications.

Farsight’s record for 24.187.234.188, the Internet address which once mapped to “printer.clintonemail.com”.

I should emphasize here that it’s unclear whether an Internet-capable printer was ever connected to printer.clintonemail.com. Nevertheless, it appears someone set it up to work that way.

Ronald Guilmette, a private security researcher in California who prompted me to look up this information, said printing things to an Internet-based printer set up this way might have made the printer data vulnerable to eavesdropping.

“Whoever set up their home network like that was a security idiot, and it’s a dumb thing to do,” Guilmette said. “Not just because any idiot on the Internet can just waste all your toner. Some of these printers have simple vulnerabilities that leave them easy to be hacked into.”

More importantly, any emails or other documents that the Clintons decided to print would be sent out over the Internet — however briefly — before going back to the printer. And that data may have been sniffable by other customers of the same ISP, Guilmette said.

“People are getting all upset saying hackers could have broken into her server, but what I’m saying is that people could have gotten confidential documents easily without breaking into anything,” Guilmette said. “So Mrs. Clinton is sitting there, tap-tap-tapping on her computer and decides to print something out. A clever Chinese hacker could have figured out, ‘Hey, I should get my own Internet address on the same block as the Clinton’s server and just sniff the local network traffic for printer files.'”

I should note that it’s possible the Clintons were encrypting all of their private mail communications with a “virtual private network” (VPN). Other historical “passive DNS” records indicate there were additional, possibly interesting and related subdomains once directly adjacent to the aforementioned Internet address 24.187.234.188:

24.187.234.186 rosencrans.dyndns.ws

24.187.234.187 wjcoffice.com

24.187.234.187 mail.clintonemail.com

24.187.234.187 mail.presidentclinton.com

24.187.234.188 printer.clintonemail.com

24.187.234.188 printer.presidentclinton.com

24.187.234.190 sslvpn.clintonemail.com

Over the past weekend, KrebsOnSecurity began hearing from sources at multiple financial institutions who said they’d detected a pattern of fraudulent charges on customer cards that were used at various Noodles & Company locations between January 2016 and the present.

Over the past weekend, KrebsOnSecurity began hearing from sources at multiple financial institutions who said they’d detected a pattern of fraudulent charges on customer cards that were used at various Noodles & Company locations between January 2016 and the present. The 2012 breach was first exposed when a hacker posted a list of some 6.5 million unique passwords to a popular forum where members volunteer or can be hired to hack complex passwords. Forum members managed to crack some the passwords, and eventually noticed that an inordinate number of the passwords they were able to crack contained some variation of “linkedin” in them.

The 2012 breach was first exposed when a hacker posted a list of some 6.5 million unique passwords to a popular forum where members volunteer or can be hired to hack complex passwords. Forum members managed to crack some the passwords, and eventually noticed that an inordinate number of the passwords they were able to crack contained some variation of “linkedin” in them.

Redmond made the announcement almost as a footnote in its Windows 10 Experience blog, but the feature caused quite a stir when the company’s flagship operating system first debuted last summer.

Redmond made the announcement almost as a footnote in its Windows 10 Experience blog, but the feature caused quite a stir when the company’s flagship operating system first debuted last summer.