It’s not unusual for the data brokers behind people-search websites to use pseudonyms in their day-to-day lives (you would, too). Some of these personal data purveyors even try to reinvent their online identities in a bid to hide their conflicts of interest. But it’s not every day you run across a US-focused people-search network based in China whose principal owners all appear to be completely fabricated identities.

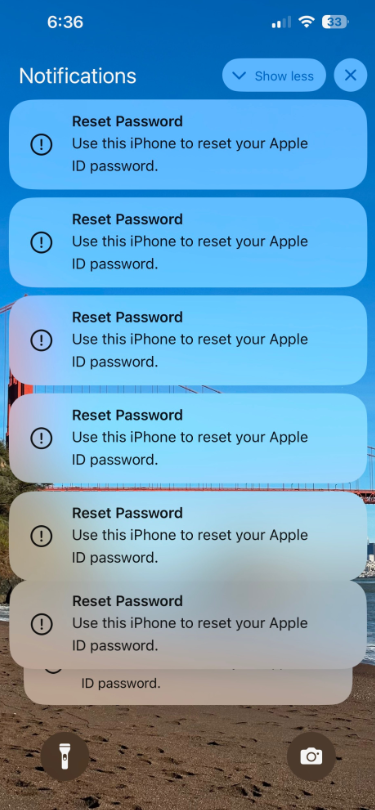

Responding to a reader inquiry concerning the trustworthiness of a site called TruePeopleSearch[.]net, KrebsOnSecurity began poking around. The site offers to sell reports containing photos, police records, background checks, civil judgments, contact information “and much more!” According to LinkedIn and numerous profiles on websites that accept paid article submissions, the founder of TruePeopleSearch is Marilyn Gaskell from Phoenix, Ariz.

The saucy yet studious LinkedIn profile for Marilyn Gaskell.

Ms. Gaskell has been quoted in multiple “articles” about random subjects, such as this article at HRDailyAdvisor about the pros and cons of joining a company-led fantasy football team.

“Marilyn Gaskell, founder of TruePeopleSearch, agrees that not everyone in the office is likely to be a football fan and might feel intimidated by joining a company league or left out if they don’t join; however, her company looked for ways to make the activity more inclusive,” this paid story notes.

Also quoted in this article is Sally Stevens, who is cited as HR Manager at FastPeopleSearch[.]io.

Sally Stevens, the phantom HR Manager for FastPeopleSearch.

“Fantasy football provides one way for employees to set aside work matters for some time and have fun,” Stevens contributed. “Employees can set a special league for themselves and regularly check and compare their scores against one another.”

Imagine that: Two different people-search companies mentioned in the same story about fantasy football. What are the odds?

Both TruePeopleSearch and FastPeopleSearch allow users to search for reports by first and last name, but proceeding to order a report prompts the visitor to purchase the file from one of several established people-finder services, including BeenVerified, Intelius, and Spokeo.

DomainTools.com shows that both TruePeopleSearch and FastPeopleSearch appeared around 2020 and were registered through Alibaba Cloud, in Beijing, China. No other information is available about these domains in their registration records, although both domains appear to use email servers based in China.

Sally Stevens’ LinkedIn profile photo is identical to a stock image titled “beautiful girl” from Adobe.com. Ms. Stevens is also quoted in a paid blog post at ecogreenequipment.com, as is Alina Clark, co-founder and marketing director of CocoDoc, an online service for editing and managing PDF documents.

The profile photo for Alina Clark is a stock photo appearing on more than 100 websites.

Scouring multiple image search sites reveals Ms. Clark’s profile photo on LinkedIn is another stock image that is currently on more than 100 different websites, including Adobe.com. Cocodoc[.]com was registered in June 2020 via Alibaba Cloud Beijing in China.

The same Alina Clark and photo materialized in a paid article at the website Ceoblognation, which in 2021 included her at #11 in a piece called “30 Entrepreneurs Describe The Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAGs) for Their Business.” It’s also worth noting that Ms. Clark is currently listed as a “former Forbes Council member” at the media outlet Forbes.com.

Entrepreneur #6 is Stephen Curry, who is quoted as CEO of CocoSign[.]com, a website that claims to offer an “easier, quicker, safer eSignature solution for small and medium-sized businesses.” Incidentally, the same photo for Stephen Curry #6 is also used in this “article” for #22 Jake Smith, who is named as the owner of a different company.

Stephen Curry, aka Jake Smith, aka no such person.

Mr. Curry’s LinkedIn profile shows a young man seated at a table in front of a laptop, but an online image search shows this is another stock photo. Cocosign[.]com was registered in June 2020 via Alibaba Cloud Beijing. No ownership details are available in the domain registration records.

Listed at #13 in that 30 Entrepreneurs article is Eden Cheng, who is cited as co-founder of PeopleFinderFree[.]com. KrebsOnSecurity could not find a LinkedIn profile for Ms. Cheng, but a search on her profile image from that Entrepreneurs article shows the same photo for sale at Shutterstock and other stock photo sites.

DomainTools says PeopleFinderFree was registered through Alibaba Cloud, Beijing. Attempts to purchase reports through PeopleFinderFree produce a notice saying the full report is only available via Spokeo.com.

Lynda Fairly is Entrepreneur #24, and she is quoted as co-founder of Numlooker[.]com, a domain registered in April 2021 through Alibaba in China. Searches for people on Numlooker forward visitors to Spokeo.

The photo next to Ms. Fairly’s quote in Entrepreneurs matches that of a LinkedIn profile for Lynda Fairly. But a search on that photo shows this same portrait has been used by many other identities and names, including a woman from the United Kingdom who’s a cancer survivor and mother of five; a licensed marriage and family therapist in Canada; a software security engineer at Quora; a journalist on Twitter/X; and a marketing expert in Canada.

Cocofinder[.]com is a people-search service that launched in Sept. 2019, through Alibaba in China. Cocofinder lists its market officer as Harriet Chan, but Ms. Chan’s LinkedIn profile is just as sparse on work history as the other people-search owners mentioned already. An image search online shows that outside of LinkedIn, the profile photo for Ms. Chan has only ever appeared in articles at pay-to-play media sites, like this one from outbackteambuilding.com.

Perhaps because Cocodoc and Cocosign both sell software services, they are actually tied to a physical presence in the real world — in Singapore (15 Scotts Rd. #03-12 15, Singapore). But it’s difficult to discern much from this address alone.

Who’s behind all this people-search chicanery? A January 2024 review of various people-search services at the website techjury.com states that Cocofinder is a wholly-owned subsidiary of a Chinese company called Shenzhen Duiyun Technology Co.

“Though it only finds results from the United States, users can choose between four main search methods,” Techjury explains. Those include people search, phone, address and email lookup. This claim is supported by a Reddit post from three years ago, wherein the Reddit user “ProtectionAdvanced” named the same Chinese company.

Is Shenzhen Duiyun Technology Co. responsible for all these phony profiles? How many more fake companies and profiles are connected to this scheme? KrebsOnSecurity found other examples that didn’t appear directly tied to other fake executives listed here, but which nevertheless are registered through Alibaba and seek to drive traffic to Spokeo and other data brokers. For example, there’s the winsome Daniela Sawyer, founder of FindPeopleFast[.]net, whose profile is flogged in paid stories at entrepreneur.org.

Google currently turns up nothing else for in a search for Shenzhen Duiyun Technology Co. Please feel free to sound off in the comments if you have any more information about this entity, such as how to contact it. Or reach out directly at krebsonsecurity @ gmail.com.

A mind map highlighting the key points of research in this story. Click to enlarge. Image: KrebsOnSecurity.com

ANALYSIS

It appears the purpose of this network is to conceal the location of people in China who are seeking to generate affiliate commissions when someone visits one of their sites and purchases a people-search report at Spokeo, for example. And it is clear that Spokeo and others have created incentives wherein anyone can effectively white-label their reports, and thereby make money brokering access to peoples’ personal information.

Spokeo’s Wikipedia page says the company was founded in 2006 by four graduates from Stanford University. Spokeo co-founder and current CEO Harrison Tang has not yet responded to requests for comment.

Intelius is owned by San Diego based PeopleConnect Inc., which also owns Classmates.com, USSearch, TruthFinder and Instant Checkmate. PeopleConnect Inc. in turn is owned by H.I.G. Capital, a $60 billion private equity firm. Requests for comment were sent to H.I.G. Capital. This story will be updated if they respond.

BeenVerified is owned by a New York City based holding company called The Lifetime Value Co., a marketing and advertising firm whose brands include PeopleLooker, NeighborWho, Ownerly, PeopleSmart, NumberGuru, and Bumper, a car history site.

Ross Cohen, chief operating officer at The Lifetime Value Co., said it’s likely the network of suspicious people-finder sites was set up by an affiliate. Cohen said Lifetime Value would investigate to determine if this particular affiliate was driving them any sign-ups.

All of the above people-search services operate similarly. When you find the person you’re looking for, you are put through a lengthy (often 10-20 minute) series of splash screens that require you to agree that these reports won’t be used for employment screening or in evaluating new tenant applications. Still more prompts ask if you are okay with seeing “potentially shocking” details about the subject of the report, including arrest histories and photos.

Only at the end of this process does the site disclose that viewing the report in question requires signing up for a monthly subscription, which is typically priced around $35. Exactly how and from where these major people-search websites are getting their consumer data — and customers — will be the subject of further reporting here.

The main reason these various people-search sites require you to affirm that you won’t use their reports for hiring or vetting potential tenants is that selling reports for those purposes would classify these firms as consumer reporting agencies (CRAs) and expose them to regulations under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

These data brokers do not want to be treated as CRAs, and for this reason their people search reports typically don’t include detailed credit histories, financial information, or full Social Security Numbers (Radaris reports include the first six digits of one’s SSN).

But in September 2023, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission found that TruthFinder and Instant Checkmate were trying to have it both ways. The FTC levied a $5.8 million penalty against the companies for allegedly acting as CRAs because they assembled and compiled information on consumers into background reports that were marketed and sold for employment and tenant screening purposes.

The FTC also found TruthFinder and Instant Checkmate deceived users about background report accuracy. The FTC alleges these companies made millions from their monthly subscriptions using push notifications and marketing emails that claimed that the subject of a background report had a criminal or arrest record, when the record was merely a traffic ticket.

The FTC said both companies deceived customers by providing “Remove” and “Flag as Inaccurate” buttons that did not work as advertised. Rather, the “Remove” button removed the disputed information only from the report as displayed to that customer; however, the same item of information remained visible to other customers who searched for the same person.

The FTC also said that when a customer flagged an item in the background report as inaccurate, the companies never took any steps to investigate those claims, to modify the reports, or to flag to other customers that the information had been disputed.

There are a growing number of online reputation management companies that offer to help customers remove their personal information from people-search sites and data broker databases. There are, no doubt, plenty of honest and well-meaning companies operating in this space, but it has been my experience that a great many people involved in that industry have a background in marketing or advertising — not privacy.

Also, some so-called data privacy companies may be wolves in sheep’s clothing. On March 14, KrebsOnSecurity published an abundance of evidence indicating that the CEO and founder of the data privacy company OneRep.com was responsible for launching dozens of people-search services over the years.

Finally, some of the more popular people-search websites are notorious for ignoring requests from consumers seeking to remove their information, regardless of which reputation or removal service you use. Some force you to create an account and provide more information before you can remove your data. Even then, the information you worked hard to remove may simply reappear a few months later.

This aptly describes countless complaints lodged against the data broker and people search giant Radaris. On March 8, KrebsOnSecurity profiled the co-founders of Radaris, two Russian brothers in Massachusetts who also operate multiple Russian-language dating services and affiliate programs.

The truth is that these people-search companies will continue to thrive unless and until Congress begins to realize it’s time for some consumer privacy and data protection laws that are relevant to life in the 21st century. Duke University adjunct professor Justin Sherman says virtually all state privacy laws exempt records that might be considered “public” or “government” documents, including voting registries, property filings, marriage certificates, motor vehicle records, criminal records, court documents, death records, professional licenses, bankruptcy filings, and more.

“Consumer privacy laws in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Virginia all contain highly similar or completely identical carve-outs for ‘publicly available information’ or government records,” Sherman said.