What Counts as “Good Faith Security Research?”

vendredi 3 juin 2022 à 21:33The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) recently revised its policy on charging violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), a 1986 law that remains the primary statute by which federal prosecutors pursue cybercrime cases. The new guidelines state that prosecutors should avoid charging security researchers who operate in “good faith” when finding and reporting vulnerabilities. But legal experts continue to advise researchers to proceed with caution, noting the new guidelines can’t be used as a defense in court, nor are they any kind of shield against civil prosecution.

In a statement about the changes, Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco said the DOJ “has never been interested in prosecuting good-faith computer security research as a crime,” and that the new guidelines “promote cybersecurity by providing clarity for good-faith security researchers who root out vulnerabilities for the common good.”

What constitutes “good faith security research?” The DOJ’s new policy (PDF) borrows language from a Library of Congress rulemaking (PDF) on the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), a similarly controversial law that criminalizes production and dissemination of technologies or services designed to circumvent measures that control access to copyrighted works. According to the government, good faith security research means:

“…accessing a computer solely for purposes of good-faith testing, investigation, and/or correction of a security flaw or vulnerability, where such activity is carried out in a manner designed to avoid any harm to individuals or the public, and where the information derived from the activity is used primarily to promote the security or safety of the class of devices, machines, or online services to which the accessed computer belongs, or those who use such devices, machines, or online services.”

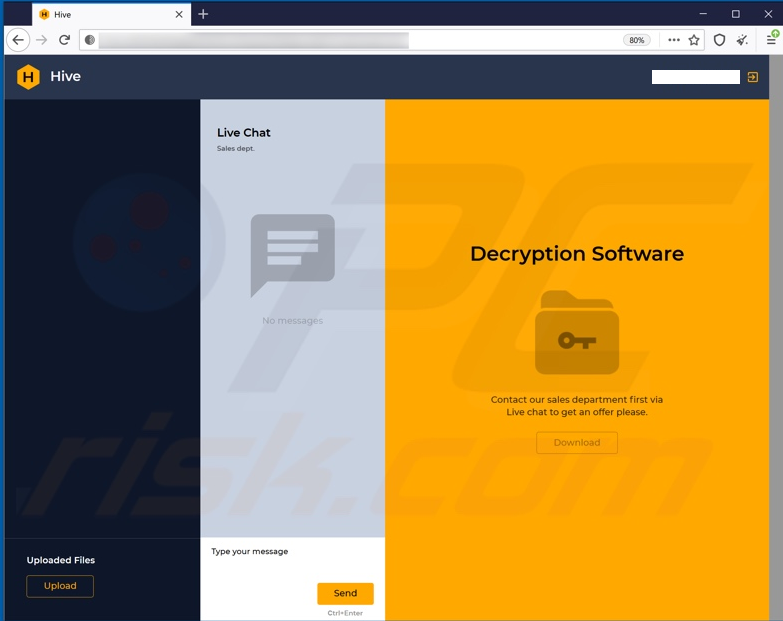

“Security research not conducted in good faith — for example, for the purpose of discovering security holes in devices, machines, or services in order to extort the owners of such devices, machines, or services — might be called ‘research,’ but is not in good faith.”

The new DOJ policy comes in response to a Supreme Court ruling last year in Van Buren v. United States (PDF), a case involving a former police sergeant in Florida who was convicted of CFAA violations after a friend paid him to use police resources to look up information on a private citizen.

But in an opinion authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the Supreme Court held that the CFAA does not apply to a person who obtains electronic information that they are otherwise authorized to access and then misuses that information.

Orin Kerr, a law professor at University of California, Berkeley, said the DOJ’s updated policy was not unexpected given the Supreme Court ruling in the Van Buren case. Kerr noted that while the new policy says one measure of “good faith” involves researchers taking steps to prevent harm to third parties, what exactly those steps might constitute is another matter.

“The DOJ is making clear they’re not going to prosecute good faith security researchers, but be really careful before you rely on that,” Kerr said. “First, because you could still get sued [civilly, by the party to whom the vulnerability is being reported], but also the line as to what is legitimate security research and what isn’t is still murky.”

Kerr said the new policy also gives CFAA defendants no additional cause for action.

“A lawyer for the defendant can make the pitch that something is good faith security research, but it’s not enforceable,” Kerr said. “Meaning, if the DOJ does bring a CFAA charge, the defendant can’t move to dismiss it on the grounds that it’s good faith security research.”

Kerr added that he can’t think of a CFAA case where this policy would have made a substantive difference.

“I don’t think the DOJ is giving up much, but there’s a lot of hacking that could be covered under good faith security research that they’re saying they won’t prosecute, and it will be interesting to see what happens there,” he said.

The new policy also clarifies other types of potential CFAA violations that are not to be charged. Most of these include violations of a technology provider’s terms of service, and here the DOJ says “violating an access restriction contained in a term of service are not themselves sufficient to warrant federal criminal charges.” Some examples include:

-Embellishing an online dating profile contrary to the terms of service of the dating website;

-Creating fictional accounts on hiring, housing, or rental websites;

-Using a pseudonym on a social networking site that prohibits them;

-Checking sports scores or paying bills at work.

ANALYSIS

Kerr’s warning about the dangers that security researchers face from civil prosecution is well-founded. KrebsOnSecurity regularly hears from security researchers seeking advice on how to handle reporting a security vulnerability or data exposure. In most of these cases, the researcher isn’t worried that the government is going to come after them: It’s that they’re going to get sued by the company responsible for the security vulnerability or data leak.

Often these conversations center around the researcher’s desire to weigh the rewards of gaining recognition for their discoveries with the risk of being targeted with costly civil lawsuits. And almost just as often, the source of the researcher’s unease is that they recognize they might have taken their discovery just a tad too far.

Here’s a common example: A researcher finds a vulnerability in a website that allows them to individually retrieve every customer record in a database. But instead of simply polling a few records that could be used as a proof-of-concept and shared with the vulnerable website, the researcher decides to download every single file on the server.

Not infrequently, there is also concern because at some point the researcher suspected that their automated activities might have actually caused stability or uptime issues with certain services they were testing. Here, the researcher is usually concerned about approaching the vulnerable website or vendor because they worry their activities may already have been identified internally as some sort of external cyberattack.

What do I take away from these conversations? Some of the most trusted and feared security researchers in the industry today gained that esteem not by constantly taking things to extremes and skirting the law, but rather by publicly exercising restraint in the use of their powers and knowledge — and by being effective at communicating their findings in a way that maximizes the help and minimizes the potential harm.

If you believe you’ve discovered a security vulnerability or data exposure, try to consider first how you might defend your actions to the vulnerable website or vendor before embarking on any automated or semi-automated activity that the organization might reasonably misconstrue as a cyberattack. In other words, try as best you can to minimize the potential harm to the vulnerable site or vendor in question, and don’t go further than you need to prove your point.