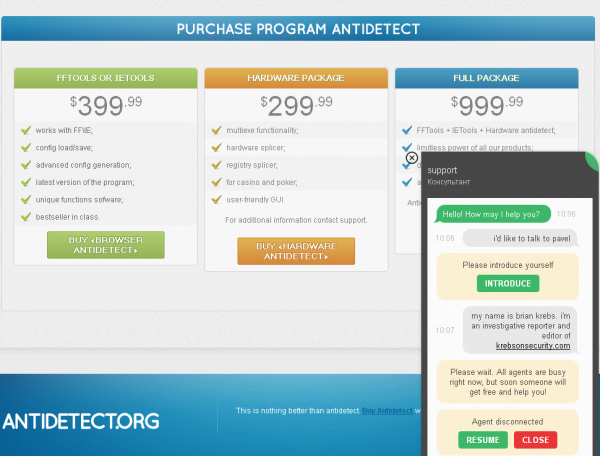

Some of the most frank and useful information about how to fight fraud comes directly from the mouths of the crooks themselves. Online cybercrime forums play a critical role here, allowing thieves to compare notes about how to evade new security roadblocks and steer clear of fraud tripwires. And few topics so reliably generate discussion on crime forums around this time of year as tax return fraud, as we’ll see in the conversations highlighted in this post.

File ‘em Before the Bad Guys Can

As several stories these past few months have noted, those involved in tax refund fraud shifted more of their activities away from the Internal Revenue Service and toward state tax filings. This shift is broadly reflected in discussions on several fraud forums from 2014, in which members lament the apparent introduction of new fraud “filters” by the IRS that reportedly made perpetrating this crime at the federal level more challenging for some scammers.

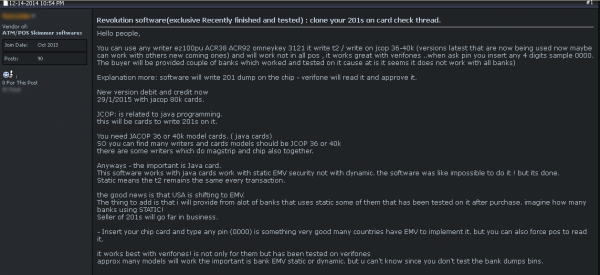

One outspoken and unrepentant tax fraudster — a ne’er-do-well using the screen name “Peleus” — reported that he had far more luck filing phony returns at the state level last year. Peleus posted the following experience to a popular fraud forum in February 2014:

“Just wanted to share a bit of my results to see if everyone is doing so bad or it just me…Federal this year has been a pain in the ass. I have about 35 applications made for federal with only 2 paid refunds…I started early in January (15-20) on TT [TurboTax] and HR [H&R Block] and made about 35 applications on Federal and State..My stats are as follows:

Federal: 35 applications (less than 10% approval rate) – average per return $2500

State: 35 apps – 15 approved (average per return $1600). State works just as great as last year, their approval rate is nearly 50% and processing time no more than 10 – 12 days.

I know that the IRS has new check filters this year but federals suck big time this year, i only got 2 refunds approved from 35 applications …all my federals are between $2300 – $2600 which is the average refund amount in the US so i wouldn’t raise any flags…I also put a small yearly salary like 25-30k….All this precautions and my results still suck big time compared to last year when i had like 30%- 35% approval rate …what the fuck changed this year? Do they check the EIN from last year’s return so you need his real employer information?”

A seasoned tax return fraudster discusses strategy.

Several seasoned members of this fraud forum responded that the IRS had indeed become more strict in validating whether the W2 information supplied by the filer had the proper Employer Identification Number (EIN), a unique tax ID number assigned to each company. The fraudsters then proceeded to discuss various ways to mine social networking sites like LinkedIn for victims’ employer information.

GET YER EINs HERE

A sidebar is probably in order here. EINs are not exactly state secrets. Public companies publish their EINs on the first page of their annual 10-K filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Still, EINs for millions of small companies here in the United States are not so easy to find, and many small business owners probably treat this information as confidential.

Nevertheless, a number of organizations specialize in selling access to EINs. One of the biggest is Dun & Bradstreet, which, as I detailed in a 2013 exposé, Data Broker Giants Hacked by ID Theft Service, was compromised for six months by a service selling Social Security numbers and other data to identity thieves like Peleus.

Last year, I heard from a source close to the investigation into the Dun & Bradstreet breach who said the thieves responsible made off with more than six million EINs. In December 2014, I asked Dun &Bradstreet about the veracity of this claim, and received a blanket statement that did not address the six million figure, but stressed that EINs are not personally identifiable information and are available to the public.

THE PREPAID MESS

By May of 2014, Peleus reported that he’d more or less worked out the best ways to avoid the IRS’s fraud filters, and was finding great success at the state level. The key, he said, was having the bogus refund sent to a unique prepaid debit card account for each filing. In this case, he found success with Green Dot — a widely-used prepaid card.

“The season is over, and my stats improved A LOT once I used one Greendot for one refund, instead of 1 checking account for 10 refunds,” he wrote.

The prepaid card industry has been an indispensable tool of tax fraudsters for several years, and remains one of the favorite means of cashing out phony refunds — as well as the proceeds from a broad range of other cybercrime activity.

At a March 12, 2015 hearing on the tax refund fraud epidemic, Utah State Tax Commission Chairman John Valentine told the U.S. Senate Finance Committee that all of the suspicious returns it has seen so far this year had the direct deposit information changed from the previous year’s bank account to prepaid debit cards — often Green Dot brand debit cards.

“Once the funds are transferred to such cards, they cannot easily be traced or recovered, a perfect vehicle to commit fraud,” Valentine told the panel. “Prepaid debit cards appear to be preferable to fraudsters because the identity thief doesn’t have to bother with banks, credit unions or check-cashing stores that may become suspicious when one person starts bringing in multiple tax refund checks to be cashed or deposited.”

Valentine said one problem his state ran into when trying to isolate filings involving prepaid cards was that there is currently no uniformity in numbering that distinguishes traditional checking and savings accounts from prepaid debit cards.

“For example, a prepaid reloadable debit card sold by Green Dot appears to be linked to a bank account even though the debit card had no actual checking or savings account associated with it,” he said in his prepared remarks (PDF). “A simple fix would be to require a different series, letter or additional numbers to distinguish these cards from cards connected to bank or credit union checking and savings accounts.”

SAFE MONEY & FREQUENT FILERS

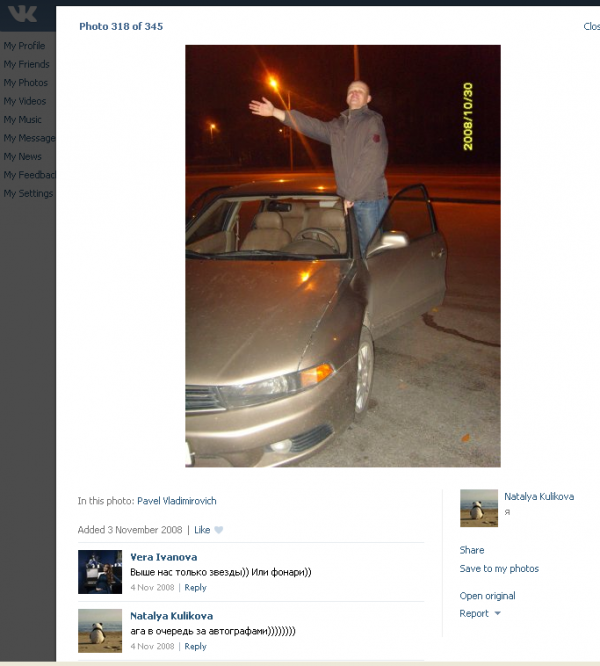

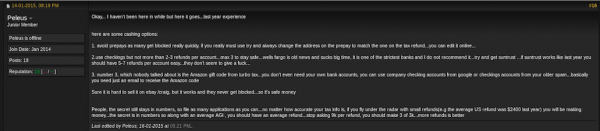

Judging from his fraud forum postings, our tax scammer Peleus was having more luck filing bogus refund requests with both the IRS and the states in this year’s tax season, which appears to have started in mid- to late January for phony filers.

Peleus’ 2015 tax tips for fellow fraudsters center around which payment instruments and banks to use and which to avoid like the plague. Peleus said prepaids are great, but getting your phony refunds deposited in a Suntrust account remains the safest option, while certain banks — particularly Wells Fargo — are to be avoided like the plague.

“Wells Fargo is old news and sucks big time,” Peleus wrote in a January 14, 2015 post. “It is one of the strictest banks and I do not recommend it. Try and get Suntrust. If Suntrust works like last year, you should have 5-7 refunds per account easy. They don’t seem to give a fuck.”

Peleus and other fraudsters continue to report strong success filing phony tax refund requests through TurboTax, the largest of the online tax preparation services — with nearly 30 million customers. Peleus urges like-minded crooks to consider asking TurboTax to credit the fraudulent refund amount as an Amazon gift code, which is apparently all the rage this year:

“You don’t even need your own bank accounts, you can use company checking accounts from Google or checking accounts from your older spam,” Peleus enthuses. “Basically, you need just an email to receive the Amazon code. Sure, it’s hard to sell it on eBay or Craigslist, but it works and they never get blocked, so it’s safe money.”

[In case you missed my recent series on how lax security and adherence to “know-your-customer” basics at TurboTax has contributed to the tax fraud epidemic, check out these stories.]

While the states and the IRS are becoming more vigilant about filtering out phony refund requests, the fraudsters are clearly responding by upping the volume of bogus filings. At least, that’s according to our virtual Virgil of the tax underworld:

“People, the secret still stays in numbers, so file as many applications as you can,” Peleus advises his fraudster friends. “No matter how accurate your tax info is, if you fly under the radar with small refunds (e.g. the average US refund was $2400 last year) you will be making money. Stop asking for $9k per refund you should make 3 of 3k, more refunds is better. Next year it will be harder I am sure, but we will all be smarter and fewer.”

ANALYSIS

Given the amount of cyber fraud that is committed with the help of the anonymity afforded to prepaid card users, the Utah State Tax Commissioner’s suggestion about requiring a unique identifier for prepaid card account numbers seems like a sound one. Certainly, the prepaid card and tax preparation industries can up their game. As I’ve noted in previous stories, both industries probably need more encouragement from federal lawmakers and/or regulators to proactively institute more robust and effective “know-your-customer” policies.

Even so, tax refund fraud is a complex problem, with many core weaknesses contributing to the overall epidemic. Not least of which is that the IRS is required to process refund requests within a very short period of receiving the filing. Very often, the IRS has to make this decision even before companies finish sending out W2 information.

In an August 2014 report to Congress on the tax refund fraud epidemic, the Government Accountability Office said that for 2014, the IRS informed taxpayers that it would generally issue refunds in less than 21 days after receiving a tax return — primarily because the IRS is required by law to pay interest if it takes longer than 45 days after the due date of the return to issue a refund.

According to a January 2015 GAO report (PDF), the IRS estimated it prevented $24.2 billion in fraudulent identity theft refunds in 2013. Unfortunately, the IRS also paid $5.8 billion that year for refund requests later determined to be fraud. The GAO noted that because of the difficulties in knowing the amount of undetected fraud, the actual amount could far exceed those estimates.

Further reading:

What Tax Fraud Victims Can Do.

All KrebsOnSecurity stories about tax refund fraud.

Update, Mar. 26, 4:56 p.m. ET: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Green Dot was managed by GE Money Bank. The latter sold part of its pre-praid business (Wal-Mart Money Card) to Green Dot back in 2013.