San Francisco Rail System Hacker Hacked

mardi 29 novembre 2016 à 06:17The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) was hit with a ransomware attack on Friday, causing fare station terminals to carry the message, “You Hacked. ALL Data Encrypted.” Turns out, the miscreant behind this extortion attempt got hacked himself this past weekend, revealing details about other victims as well as tantalizing clues about his identity and location.

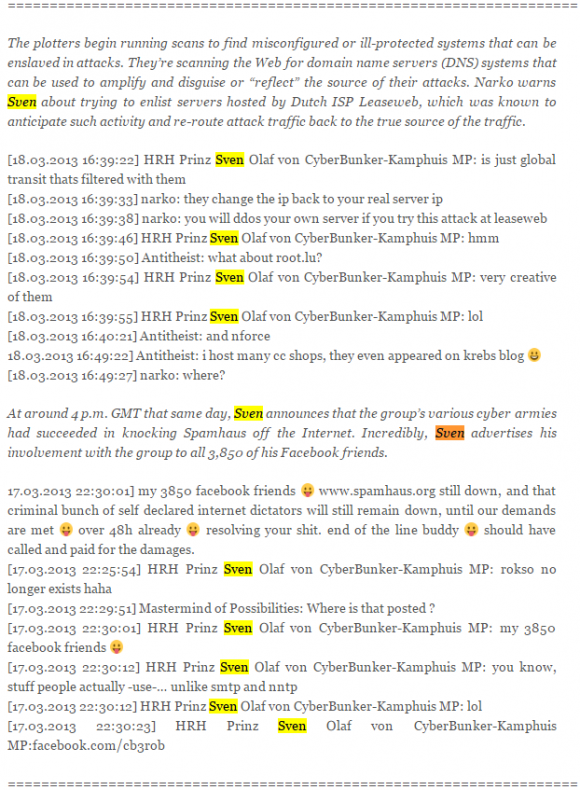

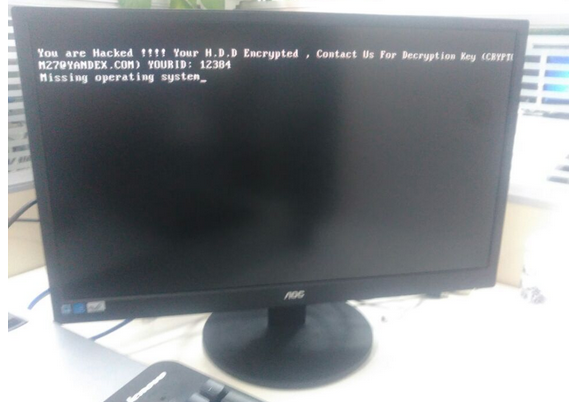

A copy of the ransom message left behind by the “Mamba” ransomware.

On Friday, The San Francisco Examiner reported that riders of SFMTA’s Municipal Rail or “Muni” system were greeted with handmade “Out of Service” and “Metro Free” signs on station ticket machines. The computer terminals at all Muni locations carried the “hacked” message: “Contact for key (cryptom27@yandex.com),” the message read.

The hacker in control of that email account said he had compromised thousands of computers at the SFMTA, scrambling the files on those systems with strong encryption. The files encrypted by his ransomware, he said, could only be decrypted with a special digital key, and that key would cost 100 Bitcoins, or approximately USD $73,000.

On Monday, KrebsOnSecurity was contacted by a security researcher who said he hacked this very same cryptom27@yandex.com inbox after reading a news article about the SFMTA incident. The researcher, who has asked to remain anonymous, said he compromised the extortionist’s inbox by guessing the answer to his secret question, which then allowed him to reset the attacker’s email password. A screen shot of the user profile page for cryptom27@yandex.com shows that it was tied to a backup email address, cryptom2016@yandex.com, which also was protected by the same secret question and answer.

Copies of messages shared with this author from those inboxes indicate that on Friday evening, Nov. 25, the attacker sent a message to SFMTA infrastructure manager Sean Cunningham with the following demand (the entirety of which has been trimmed for space reasons), signed with the pseudonym “Andy Saolis.”

“if You are Responsible in MUNI-RAILWAY !

All Your Computer’s/Server’s in MUNI-RAILWAY Domain Encrypted By AES 2048Bit!

We have 2000 Decryption Key !

Send 100BTC to My Bitcoin Wallet , then We Send you Decryption key For Your All Server’s HDD!!”

One hundred Bitcoins may seem like a lot, but it’s apparently not far from a usual payday for this attacker. On Nov. 20, hacked emails show that he successfully extorted 63 bitcoins (~$45,000) from a U.S.-based manufacturing firm.

The attacker appears to be in the habit of switching Bitcoin wallets randomly every few days or weeks. “For security reasons” he explained to some victims who took several days to decide whether to pay the ransom they’d been demanded. A review of more than a dozen Bitcoin wallets this criminal has used since August indicates that he has successfully extorted at least $140,000 in Bitcoin from victim organizations.

That is almost certainly a conservative estimate of his overall earnings these past few months: My source said he was unable to hack another Yandex inbox used by this attacker between August and October 2016, “w889901665@yandex.com,” and that this email address is tied to many search results for tech help forum postings from people victimized by a strain of ransomware known as Mamba.

Copies of messages shared with this author answer many questions raised by news media coverage of this attack, such as whether the SFMTA was targeted. In short: No. Here’s why.

Messages sent to the attacker’s cryptom2016@yandex.com account show a financial relationship with at least two different hosting providers. The credentials needed to manage one of those servers were also included in the attacker’s inbox in plain text, and my source shared multiple files from that server.

KrebsOnSecurity sought assistance from several security experts in making sense of the data shared by my source. Alex Holden, chief information security officer at Hold Security Inc, said the attack server appears to have been used as a staging ground to compromise new systems, and was equipped with several open-source tools to help find and infect new victims.

“It appears our attacker has been using a number of tools which enabled the scanning of large portions of the Internet and several specific targets for vulnerabilities,” Holden said. “The most common vulnerability used ‘weblogic unserialize exploit’ and especially targeted Oracle Corp. server products, including Primavera project portfolio management software.”

According to a review of email messages from the Cryptom27 accounts shared by my source, the attacker routinely offered to help victims secure their systems from other hackers for a small number of extra Bitcoins. In one case, a victim that had just forked over a 20 Bitcoin ransom seemed all too eager to pay more for tips on how to plug the security holes that got him hacked. In return, the hacker pasted a link to a Web server, and urged the victim to install a critical security patch for the company’s Java applications.

“Read this and install patch before you connect your server to internet again,” the attacker wrote, linking to this advisory that Oracle issued for a security hole that it plugged in November 2015.

In many cases, the extortionist told victims their data would be gone forever if they didn’t pay the ransom in 48 hours or less. In other instances, he threatens to increase the ransom demand with each passing day.

WHO IS ALI REZA?

The server used to launch the Oracle vulnerability scans offers tantalizing clues about the geographic location of the attacker. That server kept detailed logs about the date, time and Internet address of each login. A review of the more than 300 Internet addresses used to administer the server revealed that it has been controlled almost exclusively from Internet addresses in Iran. Another hosting account tied to this attacker says his contact number is +78234512271, which maps back to a mobile phone provider based in Russia.

But other details from the attack server indicate that the Russian phone number may be a red herring. For example, the attack server’s logs includes the Web link or Internet address of each victimized server, listing the hacked credentials and short notations apparently made next to each victim by the attacker. Google Translate had difficulty guessing which language was used in the notations, but a fair amount of searching indicates the notes are transliterated Farsi or Persian, the primary language spoken in Iran and several other parts of the Middle East.

User account names on the attack server hold other clues, with names like “Alireza,” “Mokhi.” Alireza may pertain to Ali Reza, the seventh descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, or just to a very common name among Iranians, Arabs and Turks.

The targets successfully enumerated as vulnerable by the attacker’s scanning server include the username and password needed to remotely access the hacked servers, as well as the IP address (and in some cases domain name) of the victim organization. In many cases, victims appeared to use newly-registered email addresses to contact the extortionist, perhaps unaware that the intruder had already done enough reconnaissance on the victim organization to learn the identity of the company and the contact information for the victim’s IT department.

The list of victims from our extortionist shows that the SFMTA was something of an aberration. The vast majority of organizations victimized by this attacker were manufacturing and construction firms based in the United States, and most of those victims ended up paying the entire ransom demanded — generally one Bitcoin (currently USD $732) per encrypted server.

Emails from the attacker’s inbox indicate some victims managed to negotiate a lesser ransom. China Construction of America Inc., for example, paid 24 Bitcoins (~$17,500) on Sunday, Nov. 27 to decrypt some 60 servers infected with the same ransomware — after successfully haggling the attacker down from his original demand of 40 Bitcoins. Other construction firms apparently infected by ransomware attacks from this criminal include King of Prussia, Pa. based Irwin & Leighton; CDM Smith Inc. in Boston; Indianapolis-based Skillman; and the Rudolph Libbe Group, a construction consulting firm based in Walbridge, Ohio. It’s unclear whether any of these companies paid a ransom to regain access to their files.

PROTECT YOURSELF AND YOUR ORGANIZATION

The data leaked from this one actor shows how successful and lucrative ransomware attacks can be, and how often victims pay up. For its part, the SFMTA said it never never considered paying the ransom.

“We have an information technology team in place that can restore our systems and that is what they are doing,” said SFMTA spokesman Paul Rose. “Existing backup systems allowed us to get most affected computers up and running this morning, and our information technology team anticipates having the remaining computers functional in the next two days.”

As the SFMTA’s experience illustrates, having proper and regular backups of your data can save you bundles. But unsecured backups can also be encrypted by ransomware, so it’s important to ensure that backups are not connected to the computers and networks they are backing up. Examples might include securing backups in the cloud or physically storing them offline. It should be noted, however, that some instances of ransomware can lock cloud-based backups when systems are configured to continuously back up in real-time.

That last tip is among dozens offered by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which has been warning businesses about the dangers of ransomware attacks for several years now. For more tips on how to avoid becoming the next ransomware victim, check out the FBI’s most recent advisory on ransomware.

Finally, as I hope this story shows, truthfully answering secret questions is a surefire way to get your online account hacked. Personally, I try to avoid using vital services that allow someone to reset my password if they can guess the answers to my secret questions. But in some cases — as with United Airlines’s atrocious new password system — answering secret questions is unavoidable. In cases where I’m allowed to type in the answer, I always choose a gibberish or completely unrelated answer that only I will know and that cannot be unearthed using social media or random guessing.