Phishers Target Anti-Money Laundering Officers at U.S. Credit Unions

vendredi 8 février 2019 à 13:58A highly targeted, malware-laced phishing campaign landed in the inboxes of multiple credit unions last week. The missives are raising eyebrows because they were sent only to specific anti-money laundering contacts at credit unions, and many credit union sources say they suspect the non-public data may have been somehow obtained from the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), an independent federal agency that insures deposits at federally insured credit unions.

The USA Patriot Act, passed in the wake of the terror attacks of Sept 11, 2001, requires all financial institutions to appoint at least two Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) contacts responsible for reporting suspicious financial transactions that may be associated with money laundering. U.S. credit unions are required to register these BSA officers with the NCUA.

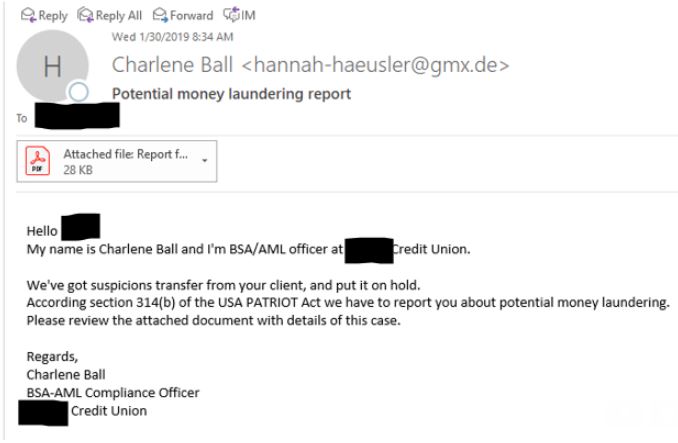

On the morning of Wednesday, Jan. 30, BSA officers at credit unions across the nation began receiving emails spoofed to make it look like they were sent by BSA officers at other credit unions. The missives addressed each contact by name, claimed that a suspicious transfer from one of the recipient credit union’s customers was put on hold for suspected money laundering, and encouraged recipients to open an attached PDF to review the suspect transaction.

One of the many variations on the malware-laced targeted phishing email sent to dozens of credit unions across the nation last week.

The phishing emails contained grammatical errors and were sent from email addresses not tied to the purported sending credit union. It is not clear if any of the BSA officers who received the messages actually clicked on the attachment, although one credit union source reported speaking with a colleague who feared a BSA contact at their institution may have fallen for the ruse.

One source at an association that works with multiple credit unions who spoke with KrebsOnSecurity on condition of anonymity said many credit unions are having trouble imagining another source for the recipient list other than the NCUA.

“I tried to think of any public ways that the scammers might have received a list of BSA officers, but sites like LinkedIn require contact through the site itself,” the source said. “CUNA [the Credit Union National Association] has BSA certification schools, but they certify state examiners and trade association staff (like me), so non-credit union employees that utilize the school should have received these emails if the list came from them. As far as we know, only credit union BSA officers have received the emails. I haven’t seen anyone who received the email say they were not a BSA officer yet.”

“Wonder where they got the list of BSA contacts at all of our credit unions,” said another credit union source. “They sent it to our BSA officer, and [omitted] said they sent it to her BSA officers.” A BSA officer at a different credit union said their IT department had traced the source of the message they received back to Ukraine.

The NCUA has not responded to multiple requests for comment since Monday. The agency’s instructions for mandatory BSA reporting (PDF) state that the NCUA will not release BSA contact information to the public. Officials with CUNA also did not respond to requests for comment.

A notice posted by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) said the bureau was aware of the phishing campaign, and was urging financial institutions to disregard the missives.

The latest scam comes amid a significant rise in successful phishing attacks, according to a non-public alert sent in late January by the U.S. Secret Service to financial institutions nationwide. “The Secret Service is observing a noticeable increase in successful large-scale phishing attacks targeting unsuspecting victims across industry,” the alert warns.

The Secret Service alert reminds readers that we in the United States are entering tax season, which typically brings a large spike in scams designed to siphon personal and financial data. It also includes some helpful reminders, including:

-Never click on links embedded in emails or open any attachments from unknown or suspect fraudulent email accounts.

-Always independently verify any requested information originates from a legitimate source.

-Visit Web sites by entering the domain name yourself (for sensitive sites, preferably by using a bookmark you created previously).

-If you are contacted via phone, hang up, look up the number for the institution at that institution’s Web site, and call back. Do not give out information in an unsolicited phone call.