Network Hijackers Exploit Technical Loophole

jeudi 13 novembre 2014 à 18:36Spammers have been working methodically to hijack large chunks of Internet real estate by exploiting a technical and bureaucratic loophole in the way that various regions of the globe keep track of the world’s Internet address ranges.

Last week, KrebsOnSecurity featured an in-depth piece about a well-known junk email artist who acknowledged sending from two Bulgarian hosting providers. These two providers had commandeered tens of thousands of Internet addresses from ISPs around the globe, including Brazil, China, India, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, Taiwan and Vietnam.

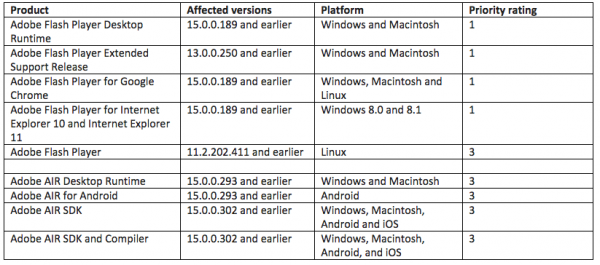

For example, a closer look at the Internet addresses hijacked by one of the Bulgarian providers — aptly named “Mega-Spred” with an email contact of “abuse@grimhosting” — shows that this provider has been slowly gobbling up far-flung IP address ranges since late August 2014.

This table, with data from the RIPE NCC — of the regional Internet Registries, shows IP address hijacking activity by Bulgarian host Mega-Spred.

According to several security and anti-spam experts who’ve been following this activity, Mega-Spred and the other hosting provider in question (known as Kandi EOOD) have been taking advantage of an administrative weakness in the way that some countries and regions of the world keep tabs on the IP address ranges assigned to various hosting providers and ISPs. Neither Kandi nor Mega-Spred responded to requests for comment.

IP address hijacking is hardly a new phenomenon. Spammers sometimes hijack Internet address ranges that go unused for periods of time. Dormant or “unannounced” address ranges are ripe for abuse partly because of the way the global routing system works: Miscreants can “announce” to the rest of the Internet that their hosting facilities are the authorized location for given Internet addresses. If nothing or nobody objects to the change, the Internet address ranges fall into the hands of the hijacker.

Experts say the hijackers also are exploiting a fundamental problem with record-keeping activities of RIPE NCC, the regional Internet registry (RIR) that oversees the allocation and registration of IP addresses for Europe, the Middle East and parts of Central Asia. RIPE is one of several RIRs, including ARIN (which handles mostly North American IP space) and APNIC (Asia Pacific), LACNIC (Latin America) and AFRINIC (Africa).

Ron Guilmette, an anti-spam crusader who is active in numerous Internet governance communities, said the problem is that a network owner in RIPE’s region can hijack Internet addresses that belong to network owners in regions managed by other RIRs, and if the hijackers then claim to RIPE that they’re the rightful owners of those hijacked IP ranges, RIPE will simply accept that claim without verifying or authenticating it.

Worse yet, Guilmette and others say, those bogus entries — once accepted by RIPE — get exported to other databases that are used to check the validity of global IP address routing tables, meaning that parties all over the Internet who are checking the validity of a route may be doing so against bogus information created by the hijacker himself.

“RIPE is now acutely aware of what is going on, and what has been going on, with the blatantly crooked activities of this rogue provider,” Guilmette said. “However, due to the exceptionally clever way that the proprietors of Mega-Spred have performed their hijacks, the people at RIPE still can’t even agree on how to even undo this mess, let alone how to prevent it from happening again in the future.”

And here is where the story perhaps unavoidably warps into Geek Factor 5. For its part, RIPE said in an emailed statement to KrebsOnSecurity that the RIPE NCC has no knowledge of the agreements made between network operators or with address space holders.

“It’s important to note the distinction between an Internet Number Registry (INR) and an Internet Routing Registry (IRR). The RIPE Database (and many of the other RIR databases) combine these separate functionalities. An INR records who holds which Internet number resources, and the sub-allocations and assignments they have made to End Users.

On the other hand, an IRRcontains route and other objects — which detail a network’s policies regarding who it will peer with, along with the Internet number resources reachable through a specific ASN/network. There are 34 separate IRRs globally — therefore, this isn’t something that happens at the RIR level, but rather at the Internet Routing Registry level.”

“It is not possible therefore for the RIRs to verify the routing information entered into Internet Routing Registries or monitor the accuracy of the route objects,” the organization concluded.

Guilmette said RIPE’s response seems crafted to draw attention away from RIPE’s central role in this mess.

“That it is somewhat disingenuous, I think for this RIPE representative to wave this whole mess off as a problem with the

IRRs when in this specific case, the IRR that first accepted and then promulgated these bogus routing validation records was RIPE,” he said.

RIPE notes that network owners can reduce the occurrence of IP address hijacking by taking advantage of Resource Certification (RPKI), a free service to RIPE members and non-members that allows network operators to request a digital certificate listing the Internet number resources they hold. This allows other network operators to verify that routing information contained in this system is published by the legitimate holder of the resources. In addition, the system enables the holder to receive notifications when a routing prefix is hijacked, RIPE said.

While RPKI (and other solutions to this project, such as DNSSEC) have been around for years, obviously not all network providers currently deploy these security methods. Erik Bais, a director at A2B Internet BV — a Dutch ISP — said while broader adoption of solutions like RPKI would certainly help in the long run, one short-term fix is for RIPE to block its Internet providers from claiming routes in address ranges managed by other RIRs.

“This is a quick fix, but it will break things in the future for legitimate usage,” Bais said.

According to RIPE, this very issue was discussed at length at the recent RIPE 69 Meeting in London last week.

“The RIPE NCC is now working with the RIPE community to investigate ways of making such improvements,” RIPE said in a statement.

This is a complex problem to be sure, but I think this story is a great reminder of two qualities about Internet security in general that are fairly static (for better or worse): First, much of the Internet works thanks to the efforts of a relatively small group of people who work very hard to balance openness and ease-of-use with security and stability concerns. Second, global Internet address routing issues are extraordinarily complex — not just in technical terms but also because they also require coordination and consensus between and among multiple stakeholders with sometimes radically different geographic and cultural perspectives. Unfortunately, complexity is the enemy of security, and spammers and other ne’er-do-wells understand and exploit this gap as often as possible.