The Case for N. Korea’s Role in Sony Hack

mercredi 24 décembre 2014 à 00:21There are still many unanswered questions about the recent attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment, such as how the attackers broke in, how long they were inside Sony’s network, whether they had inside help, and how the attackers managed to steal terabytes of data without notice. To date, a sizable number of readers remain unconvinced about the one conclusion that many security experts and the U.S. government now agree upon: That North Korea was to blame. This post examines some compelling evidence from past such attacks that has helped inform that conclusion.

The last time the world saw an attack like the one that slammed SPE was on March 20, 2013, when computer networks running three major South Korean banks and two of the country’s largest television broadcasters were hit with crippling attacks that knocked them offline and left many South Koreans unable to withdraw money from ATMs. The attacks came as American and South Korean military forces were conducting joint exercises in the Korean Peninsula.

That attack relied in part on malware dubbed “Dark Seoul,” which was designed to overwrite the initial sections of an infected computer’s hard drive. The data wiping component used in the attack overwrote information on infected hard drives by repeating the words “hastati” or “principes,” depending on which version of the wiper malware was uploaded to the compromised host.

Both of those terms reference the military classes of ancient Rome: “hastati” were the younger, poorer soldiers typically on the front lines; the “principes” referred to more hardened, seasoned soldiers. According to a detailed white paper from McAfee, the attackers left a calling card a day after the attacks in the form of a web pop-up message claiming that the NewRomanic Cyber Army Team was responsible and had leaked private information from several banks and media companies and destroyed data on a large number of machines.

The message read:

“Hi, Dear Friends, We are very happy to inform you the following news. We, NewRomanic Cyber Army Team, verified our #OPFuckKorea2003. We have now a great deal of personal information in our hands. Those includes; 2.49M of [redacted by Mcafee] member table data, cms_info more than 50M from [redacted]. Much information from [redacted] Bank. We destroyed more than 0.18M of PCs. Many auth Hope you are lucky. 11th, 12th, 13th, 21st, 23rd and 27th HASTATI Detachment. Part of PRINCIPES Elements. p.s For more information, please visit www.dropbox.com login with joseph.r.ulatoski@gmail.com::lqaz@WSX3edc$RFV. Please also visit pastebin.com.”

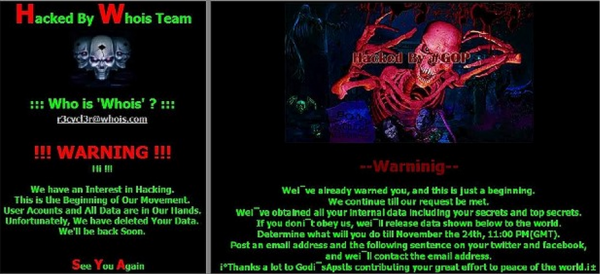

The McAfee report, and a similarly in-depth report from HP Security, mentions that another group calling itself the Whois Team — which defaced a South Korean network provider during the attack — also took responsibility for the destructive Dark Seoul attacks in 2013. But both companies say they believe the NewRomanic Cyber Army Team and the Whois Team are essentially the same group. As Russian security firm Kaspersky notes, the images used by the WhoisTeam and the warning messages left for Sony are remarkably similar:

The defacement message left by the Whois Team in the 2013 Dark Seoul attacks (left) and the message left for Sony (right).

Interestingly, the attacks on Sony also were preceded by the theft of data that was later leaked on Pastebin and via Dropbox. But how long were the attackers in the Sony case inside Sony’s network before they began wiping drives? And how did they move tens of terabytes of data off of Sony’s network without notice? Those questions remain unanswered, but the McAfee paper holds a few possible clues.

A LENGTHY CAMPAIGN

McAfee posits that, based on the compile times of the backdoor malware used to upload the drive-wiping malware, the targets in the Dark Seoul attacks were likely compromised by a remote-access Trojan delivered by a spear-phishing campaign at least two months before the data destruction began. More importantly, McAfee concludes that the data-wiping and backdoor malware used in the Dark Seoul attack was but a small component of an elaborate cyber-espionage campaign that started in 2009 and targeted only South Korean assets.

“McAfee Labs has uncovered a sophisticated military spying network targeting South Korea that has been in operation since 2009. Our analysis shows this network is connected to the Dark Seoul incident. Furthermore, we have also determined that a single group has been behind a series of threats targeting South Korea since October 2009. In this case the adversary had designed a sophisticated encrypted network designed to gather intelligence on military networks.

We have confirmed cases of Trojans operating through these networks in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2013. This network was designed to camouflage all communications between the infected systems and the control servers via the Microsoft Cryptography API using RSA 128-bit encryption. Everything extracted from these military networks would be transmitted over this encrypted network once the malware identified interesting information. What makes this case particularly interesting is the use of automated reconnaissance tools to identify what specific military information internal systems contained before the attackers tried to grab any of the files.”

The espionage malware was looking for files that contained specific terms that might indicate they harbored information about U.S. and Korean military cooperation, including “U.S. Army” and “Operation Key Resolve,” an annual military exercise held by U.S. forces and the South Korean military.

The Dark Seoul attacks were hardly an isolated incident. In 2011, the same Korean bank that was attacked in the 2013 incident was also hit with denial-of-service attacks and destructive malware. On July 4, 2009, a wave of denial-of-service attacks washed over more than two dozen Korean and U.S. Government Web sites, including the White House and the Pentagon. July 4 is Independence Day in the United States, but it also happened to be the very day that North Korea launched seven short-range missiles into the Sea of Japan in a show of military might. By the time the third wave of that attack subsided on July 9, the assailants had pushed malware to tens of thousands of zombie computers used in the assault that wiped all data from the machines.

The co-founder of CrowdStrike, a security firm that focuses heavily on identifying attribution and actors behind major cybercrime attacks, said his firm has a “very high degree of confidence that the FBI is correct in” attributing the attack against Sony Pictures to North Korean hackers, and that CrowdStrike came to this conclusion independently long before the FBI came out with its announcement last week.

“We have a high-confidence that this is a North Korean operator based on the profiles seen dating back to 2006, including prior espionage against the South Korean and U.S. government and military institutions,” said Dmitri Alperovitch, chief technology officer and co-founder at CrowdStrike.

“These events are all connected, through both the infrastructure overlap and the malware analysis, and they are connected to the Sony attack,” Alperovitch said. “We haven’t seen the skeptics produce any evidence that it wasn’t North Korea, because there is pretty good technical attribution here. I want to know how many other hacking groups are so interested in things like Key Resolve.”

Security firms like HP refer to the North Korean hacking team as the “Hastati” group, but CrowdStrike calls them by a different nickname: “Silent Chollima.” A Chollima is a mythical winged horse which originates from the Chinese classics.

“North Korea is one of the few countries that doesn’t have a real animal as a national animal,” Alperovitch said. “Which, I think, tells you a lot about the country itself.”

The “silent” part of the moniker is a reference to the stubborn fact that little is known about the hackers themselves. Unlike hacker groups in other countries where it is common to find miscreants with multiple profiles on social networks and hacker forums that can be used to build a more complete profile of the attackers — the North Koreans heavily restrict the use of Internet communications, even for their cyber warriors.

“First of all, they don’t have a ton of Internet infrastructure in North Korea, and they don’t have forums and social media which typically helps you identify, for example, whether an attack is from Russians or the Chinese,” Alperovitch said. “In general, the North Korean regime is one of the hardest intelligence targets for the intelligence and cyber attribution communities.”

On Monday, the folks at Dyn Research — a company that tracks Internet connectivity issues around the globe — said its sensors noted that North Korea inexplicably went offline on Monday, Dec. 22, at around 16:15 UTC (01:15 UTC Tuesday in the North Korean capital of Pyongyang). But the researchers stopped short of attributing a reason behind the outage.

“Who caused this, and how?,” wrote Jim Cowie, chief scientist at Dyn. “A long pattern of up-and-down connectivity, followed by a total outage, seems consistent with a fragile network under external attack. But it’s also consistent with more common causes, such as power problems.”

Interestingly, this pattern of downtime also was witnessed directly following the above-described 2013 attacks that targeted South Korean banks and media firms. According to Jason Lancaster, a security researcher at HP, the entire North Korean Internet space suffered a similar outage around the same time as the 2013 offensive against South Korea.

“When they came back online, one of those four [North Korean Internet address blocks] was routing through an Intelsat satellite connection,” Lancaster said. “What caused the 2013 outage? They never determined the cause. The speculation was that they were under attack, but there was never any proof of that happening.”

Additional reading:

US-CERT analysis of the computer worm used in the attack on Sony.

TaoSecurity Blog: What Does ‘Responsibility’ Mean for Attribution?

McAfee report on Dark Seoul attacks (PDF)

HP Security: Profiling an Enigma – The Mystery of North Korea’s Cyber Threat Landscape (PDF)