Sextortion Scam Uses Recipient’s Hacked Passwords

jeudi 12 juillet 2018 à 16:19Here’s a clever new twist on an old email scam that could serve to make the con far more believable. The message purports to have been sent from a hacker who’s compromised your computer and used your webcam to record a video of you while you were watching porn. The missive threatens to release the video to all your contacts unless you pay a Bitcoin ransom. The new twist? The email now references a real password previously tied to the recipient’s email address.

The basic elements of this sextortion scam email have been around for some time, and usually the only thing that changes with this particular message is the Bitcoin address that frightened targets can use to pay the amount demanded. But this one begins with an unusual opening salvo:

“I’m aware that <substitute password formerly used by recipient here> is your password,” reads the salutation.

The rest is formulaic:

You don’t know me and you’re thinking why you received this e mail, right?

Well, I actually placed a malware on the porn website and guess what, you visited this web site to have fun (you know what I mean). While you were watching the video, your web browser acted as a RDP (Remote Desktop) and a keylogger which provided me access to your display screen and webcam. Right after that, my software gathered all your contacts from your Messenger, Facebook account, and email account.

What exactly did I do?

I made a split-screen video. First part recorded the video you were viewing (you’ve got a fine taste haha), and next part recorded your webcam (Yep! It’s you doing nasty things!).

What should you do?

Well, I believe, $1400 is a fair price for our little secret. You’ll make the payment via Bitcoin to the below address (if you don’t know this, search “how to buy bitcoin” in Google).

BTC Address: 1Dvd7Wb72JBTbAcfTrxSJCZZuf4tsT

8V72

(It is cAsE sensitive, so copy and paste it)Important:

You have 24 hours in order to make the payment. (I have an unique pixel within this email message, and right now I know that you have read this email). If I don’t get the payment, I will send your video to all of your contacts including relatives, coworkers, and so forth. Nonetheless, if I do get paid, I will erase the video immidiately. If you want evidence, reply with “Yes!” and I will send your video recording to your 5 friends. This is a non-negotiable offer, so don’t waste my time and yours by replying to this email.

KrebsOnSecurity heard from three different readers who received a similar email in the past 72 hours. In every case, the recipients said the password referenced in the email’s opening sentence was in fact a password they had previously used at an account online that was tied to their email address.

However, all three recipients said the password was close to ten years old, and that none of the passwords cited in the sextortion email they received had been used anytime on their current computers.

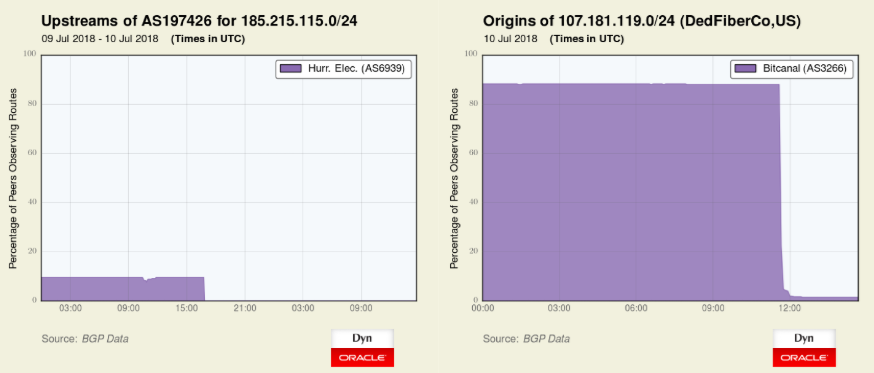

It is likely that this improved sextortion attempt is at least semi-automated: My guess is that the perpetrator has created some kind of script that draws directly from the usernames and passwords from a given data breach at a popular Web site that happened more than a decade ago, and that every victim who had their password compromised as part of that breach is getting this same email at the address used to sign up at that hacked Web site.

I suspect that as this scam gets refined even more, perpetrators will begin using more recent and relevant passwords — and perhaps other personal data that can be found online — to convince people that the hacking threat is real. That’s because there are a number of shady password lookup services online that index billions of usernames (i.e. email addresses) and passwords stolen in some of the biggest data breaches to date.

Alternatively, an industrious scammer could simply execute this scheme using a customer database from a freshly hacked Web site, emailing all users of that hacked site with a similar message and a current, working password. Tech support scammers also may begin latching onto this method as well.

Sextortion — even semi-automated scams like this one with no actual physical leverage to backstop the extortion demand — is a serious crime that can lead to devastating consequences for victims. Sextortion occurs when someone threatens to distribute your private and sensitive material if you don’t provide them with images of a sexual nature, sexual favors, or money.

According to the FBI, here are some things you can do to avoid becoming a victim:

-Never send compromising images of yourself to anyone, no matter who they are — or who they say they are.

-Don’t open attachments from people you don’t know, and in general be wary of opening attachments even from those you do know.

-Turn off [and/or cover] any web cameras when you are not using them.

The FBI says in many sextortion cases, the perpetrator is an adult pretending to be a teenager, and you are just one of the many victims being targeted by the same person. If you believe you’re a victim of sextortion, or know someone else who is, the FBI wants to hear from you: Contact your local FBI office (or toll-free at 1-800-CALL-FBI).

According to security firm

According to security firm  Adobe says the Flash update addresses “critical” security holes, meaning they could be exploited by malware or miscreants to take complete, remote control over vulnerable systems. My standard advice is for readers to kick Flash to the curb, as it’s a buggy program that is a perennial favorite target of malware purveyors.

Adobe says the Flash update addresses “critical” security holes, meaning they could be exploited by malware or miscreants to take complete, remote control over vulnerable systems. My standard advice is for readers to kick Flash to the curb, as it’s a buggy program that is a perennial favorite target of malware purveyors.