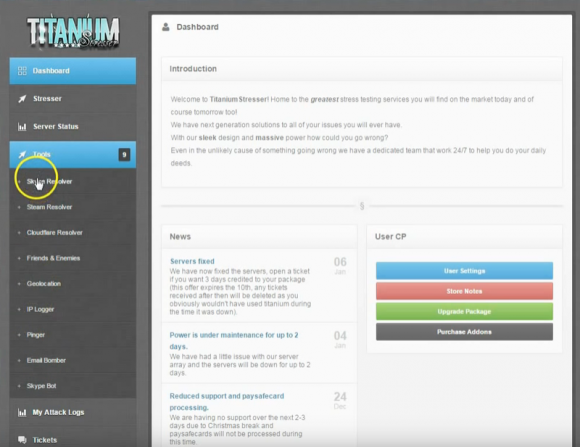

UK Man Gets Two Years in Jail for Running ‘Titanium Stresser’ Attack-for-Hire Service

mardi 25 avril 2017 à 17:06A 20-year-old man from the United Kingdom was sentenced to two years in prison today after admitting to operating and selling access to “Titanium Stresser,” a simple-to-use service that let paying customers launch crippling online attacks against Web sites and individual Internet users.

Adam Mudd of Herfordshire, U.K. admitted to three counts of computer misuse connected with his creating and operating the attack service, also known as a “stresser” or “booter” tool. Services like Titanium Stresser coordinate so-called “distributed denial-of-service” or DDoS attacks that hurl huge barrages of junk data at a site in a bid to make it crash or become otherwise unreachable to legitimate visitors.

According to U.K. prosecutors, Mudd’s Titanium Stresser service was used by others in more than 1.7 million denial-of-service attacks against victims worldwide, with most countries in the world affected at some point. He originally built the booter service at the age of 15, earning more than $300,000 in ill-gotten gains from it. Also during his interviews, he admitted security breaches against his own college while he was there studying computer science.

Mudd pleaded guilty to three offences under the U.K. Computer Misuse Act and a further offense of money laundering under the Proceeds of Crime Act in October 2016.

“Today, he was sentenced to 24 months imprisonment for his own DDoS attacks, nine months for running a titanium stressor service and 24 months for money laundering the proceeds made from the stressor service, all to run concurrently,” reads a press release issued by the Eastern Region Special Operations Unit (ERSOU), an anti-cybercrime unit that worked with the U.K.’s National Crime Agency to investigate Mudd.

Detective Chief Inspector Martin Peters of the ERSOU’s Regional Crime Unit recalled that at sentencing the judge said the defendant likely would have received six years if he’d been tried as an adult and if he had no medical issues. Mudd had been slated to be sentenced last week, but that hearing was delayed until today after the court heard medical testimony on Mudd’s apparent struggles with autism.

The Mudd case is the latest in a string of law enforcement actions in the U.K., U.S. and elsewhere targeting booter service operators and their customers. In December 2016, federal investigators in the United States and Europe arrested nearly three-dozen people suspected of patronizing booter services. That crackdown was part of an effort by authorities to weaken demand for booter and stresser services and to impress upon customers that hiring someone to launch cyberattacks on your behalf can land you in jail.

In October 2016, the U.S. Justice Department charged two 19-year-old men alleged to have run booter services tied to the “Lizard Squad” hacking group. That same month the sprawling discussion forum Hackforums — once the most bustling marketplace on the Internet where people could compare and purchase booter and stresser service subscriptions — announced that it was permanently banning the sale and advertising of booters.

Last month, authorities in Israel said they were preparing a case against two 18-year-old Israeli men who investigators there say operated the wildly popular “vDOS” booter service. The proprietors of vDOS were in business for four years prior to being exposed by KrebsOnSecurity. During just two of those four years in operation vDOS made more than $600,000 helping paying customer coordinate hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of DDoS attacks.

The detail about Mudd having attacked the very same school he was attending as a computer science student seemed both interesting and familiar. Then I remembered: This same dynamic was at work with a young man approximately Mudd’s age who lives in New Jersey and recently was implicated by many of his close associates and a great deal of circumstantial evidence as a co-author of the Mirai botnet computer code.

Mirai is a network worm that enslaves poorly secured “Internet of Things” devices like security cameras and digital video recorders for use in extremely powerful DDoS attacks capable of knocking almost any target offline.

After Mirai took my site offline for several days last year, I spent many hours trying to figure out who was responsible for writing and unleashing the malware. All signs pointed to a computer science student at Rutgers University who used a large Mirai botnet to attack the university repeatedly — all the while using his hacker alter ego to taunt the university in online interviews.

The authorities in the U.K. say they are hoping to make an example of Mudd as part of a broader education effort to divert talented, smart kids away from malicious hacking and toward more productive endeavors.

“Adam Mudd’s case is a regrettable one, because this young man clearly has a lot of skill, but he has been utilising that talent for personal gain at the expense of others,” the ERSOU press release observes. “We want to make clear it is not our wish to unnecessarily criminalise young people, but want to harness those skills before they accelerate into crime. It is important that this case sends out a clear message to others who may be tempted by committing cybercrime or who are already engaging in cyber scams from the comfort of their own bedrooms, to consider what they are doing and it is for parents to know and understand what your children are doing online.”

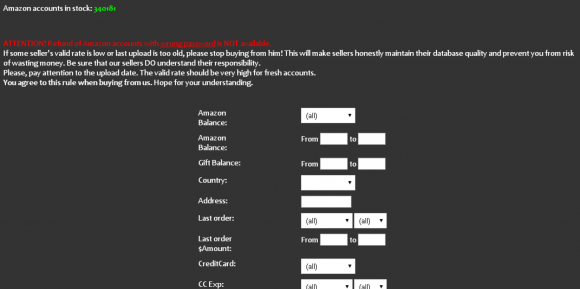

![The 2pac[dot]cc credit card shop that Seleznov operated.](./media/c5452f55.2packcc-600x365.png)

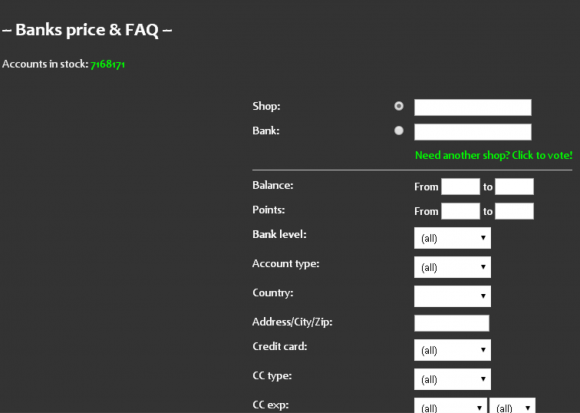

![A private mesasge between card merchant "Bulba" and an interested buyer on the fraud bazaar carder[dot]pro.](./media/3d17db45.bulbaoncarder-600x401.png)

Your average spam email can contain a great deal of information about the systems used to blast junk email. If you’re lucky, it may even offer insight into the organization that owns the networked resources (computers, mobile devices) which have been hacked for use in sending or relaying junk messages.

Your average spam email can contain a great deal of information about the systems used to blast junk email. If you’re lucky, it may even offer insight into the organization that owns the networked resources (computers, mobile devices) which have been hacked for use in sending or relaying junk messages.