Lizard Stresser Runs on Hacked Home Routers

vendredi 9 janvier 2015 à 16:17The online attack service launched late last year by the same criminals who knocked Sony and Microsoft’s gaming networks offline over the holidays is powered mostly by thousands of hacked home Internet routers, KrebsOnSecurity.com has discovered.

Just days after the attacks on Sony and Microsoft, a group of young hoodlums calling themselves the Lizard Squad took responsibility for the attack and announced the whole thing was merely an elaborate commercial for their new “booter” or “stresser” site — a service designed to help paying customers knock virtually any site or person offline for hours or days at a time. As it turns out, that service draws on Internet bandwidth from hacked home Internet routers around the globe that are protected by little more than factory-default usernames and passwords.

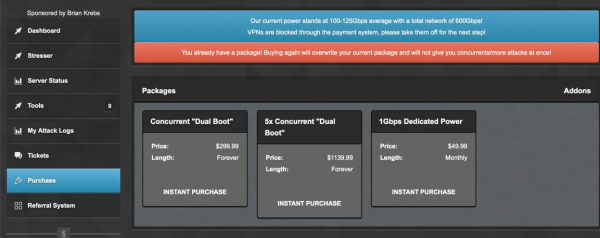

The Lizard Stresser’s add-on plans. Despite this site’s claims, it is *not* sponsored by this author.

In the first few days of 2015, KrebsOnSecurity was taken offline by a series of large and sustained denial-of-service attacks apparently orchestrated by the Lizard Squad. As I noted in a previous story, the booter service — lizardstresser[dot]su — is hosted at an Internet provider in Bosnia that is home to a large number of malicious and hostile sites.

That provider happens to be on the same “bulletproof” hosting network advertised by “sp3c1alist,” the administrator of the cybercrime forum Darkode. Until a few days ago, Darkode and LizardStresser shared the same Internet address. Interestingly, one of the core members of the Lizard Squad is an individual who goes by the nickname “Sp3c.”

On Jan. 4, KrebsOnSecurity discovered the location of the malware that powers the botnet. Hard-coded inside of that malware was the location of the LizardStresser botnet controller, which happens to be situated in the same small swath Internet address space occupied by the LizardStresser Web site (217.71.50.x)

The malicious code that converts vulnerable systems into stresser bots is a variation on a piece of rather crude malware first documented in November by Russian security firm Dr. Web, but the malware itself appears to date back to early 2014 (Google’s Chrome browser should auto-translate that page; for others, a Google-translated copy of the Dr. Web writeup is here).

As we can see in that writeup, in addition to turning the infected host into attack zombies, the malicious code uses the infected system to scan the Internet for additional devices that also allow access via factory default credentials, such as “admin/admin,” or “root/12345”. In this way, each infected host is constantly trying to spread the infection to new home routers and other devices accepting incoming connections (via telnet) with default credentials.

The botnet is not made entirely of home routers; some of the infected hosts appear to be commercial routers at universities and companies, and there are undoubtedly other devices involved. The preponderance of routers represented in the botnet probably has to do with the way that the botnet spreads and scans for new potential hosts. But there is no reason the malware couldn’t spread to a wide range of devices powered by the Linux operating system, including desktop servers and Internet-connected cameras.

KrebsOnSecurity had extensive help on this project from a team of security researchers who have been working closely with law enforcement officials investigating the LizardSquad. Those researchers, however, asked to remain anonymous in this story. The researchers who assisted on this project are working with law enforcement officials and ISPs to get the infected systems taken offline.

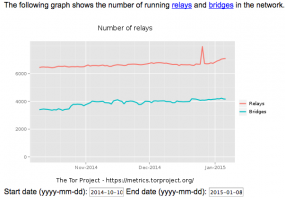

This is not the first time members of LizardSquad have built a botnet. Shortly after their attack on Sony and Microsoft, the group’s members came up with the brilliant idea to mess with the Tor network, an anonymity system that bounces users’ connections between multiple networks around the world, encrypting the communications at every step of the way. Their plan was to set up many hundreds of servers to act as Tor relays, and somehow use that access to undermine the integrity of the Tor network.

This graphic reflects a sharp uptick in Tor relays stood up at the end of 2014 in a failed bid by the Lizard Squad to mess with Tor.

According to sources close to the LizardSquad investigation, the group’s members used stolen credit cards to purchase thousands of instances of Google’s cloud computing service — virtual computing resources that can be rented by the day or longer. That scheme failed shortly after the bots were stood up, as Google quickly became aware of the activity and shut down the computing resources that were purchased with stolen cards.

A Google spokesperson said he was not able to discuss specific incidents, noting only that, “We’re aware of these reports, and have taken the appropriate actions.” Nevertheless, the incident was documented in several places, including this Pastebin post listing the Google bots that were used in the failed scheme, as well as a discussion thread on the Tor Project mailing list.

ROUTER SECURITY 101

Wireless and wired Internet routers are very popular consumer devices, but few users take the time to make sure these integral systems are locked down tightly. Don’t make that same mistake. Take a few minutes to review these tips for hardening your hardware.

For starters, make sure you change the default credentials on the router. This is the username and password that were factory installed by the router maker. The administrative page of most commercial routers can be accessed by typing 192.168.1.1, or 192.168.0.1 into a Web browser address bar. If neither of those work, try looking up the documentation at the router maker’s site, or checking to see if the address is listed here. If you still can’t find it, open the command prompt (Start > Run/or Search for “cmd”) and then enter ipconfig. The address you need should be next to Default Gateway under your Local Area Connection.

For starters, make sure you change the default credentials on the router. This is the username and password that were factory installed by the router maker. The administrative page of most commercial routers can be accessed by typing 192.168.1.1, or 192.168.0.1 into a Web browser address bar. If neither of those work, try looking up the documentation at the router maker’s site, or checking to see if the address is listed here. If you still can’t find it, open the command prompt (Start > Run/or Search for “cmd”) and then enter ipconfig. The address you need should be next to Default Gateway under your Local Area Connection.

If you don’t know your router’s default username and password, you can look it up here. Leaving these as-is out-of-the-box is a very bad idea. Most modern routers will let you change both the default user name and password, so do both if you can. But it’s most important to pick a strong password.

When you’ve changed the default password, you’ll want to encrypt your connection if you’re using a wireless router (one that broadcasts your modem’s Internet connection so that it can be accessed via wireless devices, like tablets and smart phones). Onguardonline.gov has published some video how-tos on enabling wireless encryption on your router. WPA2 is the strongest encryption technology available in most modern routers, followed by WPA and WEP (the latter is fairly trivial to crack with open source tools, so don’t use it unless it’s your only option).

But even users who have a strong router password and have protected their wireless Internet connection with a strong WPA2 passphrase may have the security of their routers undermined by security flaws built into these routers. At issue is a technology called “Wi-Fi Protected Setup” (WPS) that ships with many routers marketed to consumers and small businesses. According to the Wi-Fi Alliance, an industry group, WPS is “designed to ease the task of setting up and configuring security on wireless local area networks. WPS enables typical users who possess little understanding of traditional Wi-Fi configuration and security settings to automatically configure new wireless networks, add new devices and enable security.”

But even users who have a strong router password and have protected their wireless Internet connection with a strong WPA2 passphrase may have the security of their routers undermined by security flaws built into these routers. At issue is a technology called “Wi-Fi Protected Setup” (WPS) that ships with many routers marketed to consumers and small businesses. According to the Wi-Fi Alliance, an industry group, WPS is “designed to ease the task of setting up and configuring security on wireless local area networks. WPS enables typical users who possess little understanding of traditional Wi-Fi configuration and security settings to automatically configure new wireless networks, add new devices and enable security.”

But WPS also may expose routers to easy compromise. Read more about this vulnerability here. If your router is among those listed as vulnerable, see if you can disable WPS from the router’s administration page. If you’re not sure whether it can be, or if you’d like to see whether your router maker has shipped an update to fix the WPS problem on their hardware, check this spreadsheet. If your router maker doesn’t offer a firmware fix, consider installing an open source alternative, such as DD-WRT (my favorite) or Tomato.

While you’re monkeying around with your router setting, consider changing the router’s default DNS servers to those maintained by OpenDNS. The company’s free service filters out malicious Web page requests at the domain name system (DNS) level. DNS is responsible for translating human-friendly Web site names like “example.com” into numeric, machine-readable Internet addresses. Anytime you send an e-mail or browse a Web site, your machine is sending a DNS look-up request to your Internet service provider to help route the traffic.

While you’re monkeying around with your router setting, consider changing the router’s default DNS servers to those maintained by OpenDNS. The company’s free service filters out malicious Web page requests at the domain name system (DNS) level. DNS is responsible for translating human-friendly Web site names like “example.com” into numeric, machine-readable Internet addresses. Anytime you send an e-mail or browse a Web site, your machine is sending a DNS look-up request to your Internet service provider to help route the traffic.

Most Internet users use their ISP’s DNS servers for this task, either explicitly because the information was entered when signing up for service, or by default because the user hasn’t specified any external DNS servers. By creating a free account at OpenDNS.com, changing the DNS settings on your machine, and registering your Internet address with OpenDNS, the company will block your computer from communicating with known malware and phishing sites. OpenDNS also offers a fairly effective adult content filtering service that can be used to block porn sites on an entire household’s network.

The above advice on router security was taken from a broader tutorial on how to stay safe online, called “Tools for a Safer PC.”